Rock Island Mother Treasures Time As a Foster Care Volunteer

Carrie McGuire of Rock Island and her husband have two adult children (ages 26 and 24), but for the past three years, she’s spent many hours training and volunteering to help two foster families, serving six young children.

Carrie McGuire of Rock Island (with husband Charlie) is a CASA volunteer.

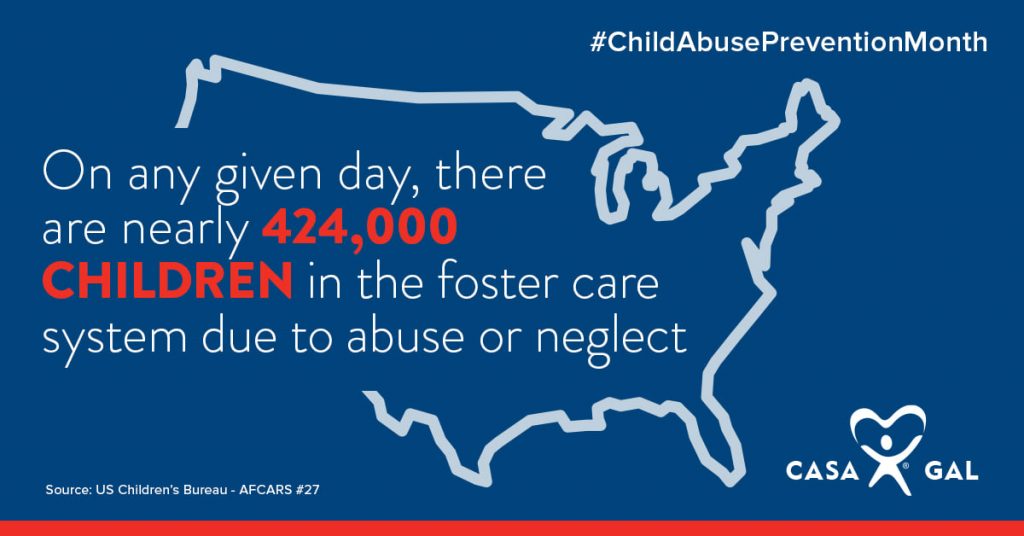

McGuire is one of 19 Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA), a program coordinated by the Child Abuse Council, serving Rock Island County. CASA is a national organization that trains community volunteers to be a voice and advocate for children in foster care. Before four new volunteers recently started, the local CASA had 15 advocates serving 30 children, but there are now 294 children in foster care in Rock Island County, and the need for more volunteers is great.

“I saw an ad in the newspaper, and I carried it around and it kind of jumped out at me and I’m like, this sounds like a really cool opportunity completely out of my comfort zone,” McGuire, 55, said recently. “I really didn’t have any have any experience in in that world.”

CASA volunteers are trained over nine weeks (for three hours a week) and then assigned to a case by the court to be a voice for that child in care, said Daniel Williams, advocate specialist for the Child Abuse Council CASA program. “Volunteer advocates meet with the child and all parties interested in the case to get the full story of what the child is going through during their time in the foster care system and then advocate for that child in court.”

The current CASA program serving Rock Island County has been coordinated by the Child Abuse Council since 2018.

In addition to caseworkers and social workers, the CASA acts as an extra voice to support and represent the children, working toward the goal of getting them in a permanent, safe home, he said.

The national Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA)/Guardian Ad Litem (GAL) Association for Children, together with its state and local members, supports and promotes court-appointed volunteer advocacy so that every abused and neglected child can be safe, establish permanence and have the opportunity to thrive.

Nationwide, there are 948 affiliated chapters and organizations in 49 states, with 96,929 volunteers serving 276,809 kids annually, according to https://nationalcasagal.org/.

No special background or education is required to become a CASA volunteer. They encourage people from all cultures and professions, and of all ethnic and educational backgrounds.

A group of CASA volunteers with Judge Ted Kutsunis.

Once accepted into the program, volunteers are trained in courtroom procedure, the social service system and the inner workings of the juvenile court system. Understanding more about family dynamics and the development of children is also discussed during training.

“The training was very intensive and I learned a lot,” McGuire said. “It was really pretty eye-opening, because there was a lot I didn’t know and I didn’t know what I didn’t know till I got into the training and once I saw what the need was, I mean that made it even more meaningful to me that to continue with the program.”

She sees two families regularly – each with three kids, one ranging ages 6-12 (placed with their maternal grandparents) and the other a 5-year-old and 4-year-old twins, who were with their maternal aunt. The latter siblings were returned home to their biological parents in March 2021, but CASAs remain on the case for six months post-return, McGuire said.

“Just to like still be there as a resource, still check-in, still do home visits every month just to make sure they still have the full support team, even though they’re at home,” she said. “So we’ll stay on the case till the end of September, as long as things are going well.

A group of CASA volunteers with Judge Ted Kutsunis.

CASA volunteers are required to write a status report on the children that can be used any time there is a court hearing, and the program offers a template for those, so it’s straightforward what is needed, Williams said.

Juvenile court happens every three to six months and volunteers write a court report for the judge, at all the main court hearings, he said. The juvenile judge assigns CASAs to selected foster-care cases, where they could use an additional advocate, Williams said. The report also is given to others involved in the case, like attorneys and caseworkers.

After the new CASAs started, the judge assigned them new cases, he said. There are a couple CASAs that have two cases each (like McGuire), but that is rare. One volunteer usually has one family, which can have multiple siblings.

“We have CASAs who meet more often than once a month,” Williams said. “We have CASAs that are in regular contact with the family, whether that’s texting or calling, just to be able to check in. So it’s around 10 to 15 hours a month, and obviously that’s gonna change depending on where he case is, if there’s a lot happening.”

Daniel Williams (right), advocate specialist with Child Abuse Council, and CASA volunteers.

“Unfortunately, it can get a little frustrating sometimes at how slow things move,” McGuire said. “I understand that these caseworkers, the social workers are very overwhelmed. And here’s me, I have two cases, and they may have 30 cases on their caseload. And, I mean, it takes a long time because the juvenile court, it just takes a long time for things to get scheduled and things to get accomplished.”

“There have been some assessments that the parents need to do, and families want their children back and they know that there are some things they need to do,” she said. “It may take six months to get on the schedule to get these assessments. So everything is just kind of kicked down the road a little bit further and that was a big learning curve for me.

“The services that some of these kids need and the things that they need to help them cope — it’s very difficult to get some of that stuff done for these kids too,” McGuire said. “Everybody’s doing the best they with limitations that they have. It’s just hard to get everything scheduled that they need. There is still just such a backlog, a shortage of certain services.”

In one of her families, the kids have two biological parents, and in the other, the five-year-old has one father and the twins are by another father. “So the five-year-old needs to go with his dad a couple of days a week and then that the twins go with their dad and so yeah, that one’s a little more convoluted,” she said.

CASA volunteers do not need to have any special background to participate, and get about 30 hours of training.

Complications from coping with Covid

McGuire typically sees each family at least once a month.

“I check in and offer support where I can like, for example, the five-year-old is getting ready to start kindergarten in the fall,” she said. “So I’m helping them out with getting them school supplies, to get him everything he needs.” “Or just kind of helping them keep focus, so he’s ready when school starts,” McGuire said. “With Covid-19 last year, preschool was not a good scenario for him. I just want to make sure that he’s well prepared for when school starts.”

It was also a challenge since March 2020 for more than a year to be forced to have virtual meetings with children, usually over Zoom or FaceTime, McGuire said.

“When the weather was nice, we would talk outside,” she said. “Lately, it’s been a lot easier to meet in person. Now it isn’t as big of a barrier so we’ve been meeting live in person for a while now.”

“When I go for a visit, I will visit obviously with the foster parents and with the bio parents, if they’re around too, but my primary objective is to talk to the kids,” McGuire said. “My role is to be a voice for the people that don’t have the voice. So we have to write court reports the same as the social workers do, and it’s kind of boring because I feel like our assessments may be different than what the social workers’ assessments are, but I feel like our court reports matter.

“I feel like the judge is taking what we say — our insights and our feedback, he’s taking those into consideration when he’s making decisions as well.,” she said.

In the year-plus during Covid, the CASA contact was more on Zoom or outdoors (with masks, socially distanced), Williams agreed. “We still found ways to stay in touch – whether it was Zoom, whether it was phone calls, finding ways to stay in touch,” he said. “It was different, but the advocacy and the work still continued during this time of social distancing and the pandemic.”

McGuire said CASA has increased her appreciation for the value foster parents provide in society.

At any one time, there are 424,000 children in the U.S. foster care system, including 294 in Rock Island County.

“Especially like this past year, with kids having to do a lot of virtual learning for the longest time,” she said, noting the one family with school-age kids being taken care of by grandparents.

“You had three kids at home all trying to do virtual learning and the limitations of connectivity,” McGuire said. “Internet was an issue and just keeping the kids engaged and helping them with their school work, being grandparents and trying to have three kids, to keep them focused on school work. I have a total appreciation for it. And it’s their family, but I mean, it’s still hard. I think Covid-19 was hard on families in general. But particularly people that are that are trying to foster kids.”

She gets most satisfaction from the relationships she’s made.

“I like getting the kids to trust me because, going into a house, they don’t know me from anybody and just trying to make sure they know that I’m there just to talk to them,” McGuire said. “And then I’m there for them and then I’m someone that they can talk to if they need to. But it’s really feeling like I’m contributing and bringing value too, and I help the families out and so that they know that that my goal is the same as theirs and hopefully to get the families back together.”

Though she’s there to observe, McGuire never writes anything down while doing a home visit.

“I don’t want them to feel like I’m interrogating them or I’m interviewing them,” she said. “I’m just there to visit with them and I take a game. And if I show up without something to do there, they’re looking at me like I have grown a third head. We just, we play games, we interact. We talk and it’s just easier to talk to them and ask them questions.

“You get insights from them when we’re playing a game or we’ve done things like we’ve made friendship bracelets, things like that,” McGuire said. “I try to make it very non-confrontational, non-intrusive. I just want them to know that that I’m there for them. And I just want to make sure that they understand it, the families understand that I’m doing what’s in the best interest of life.”

“I’ve never felt like I was out there on my own. When I first got trained, they offered to go with you – so there was kind of like a warm introduction, like this is Carrie.”

“For the caseworkers, I didn’t think that I was down there to assess them. I’m not there to judge anybody,” she said. “I’m just there to help out and be another resource for the kids. Once everyone understood what my role was, it got a lot more comfortable, but it was nice to kind of go in with the caseworker. So she could introduce me and you realize that we were all on the same team and working towards the same goal.”

“I felt like I was trained and equipped, and had everything I needed to do, to do a job role,” McGuire said. “The training is long, but the time commitment is not horrible, and if you feel like you want to do something to give back to your community, it is hard, but it’s a rewarding at the end of the day, when you feel like you’ve helped or you’ve made a difference or you’ve made a connection, it feels good.”

She prefers meeting the kids in person, versus virtually.

“The kids, especially if the kids are littler, their attention span is very short and they really don’t want to be on FaceTime with me,” McGuire said. “At least I’m playing a game with them or coloring or painting, or doing sidewalk chalk. At least they’re in the moment and we can chat a little more.”

Nationally, there are 948 CASA programs in 49 states, with nearly 97,000 volunteers.

Next volunteer training starts in August

The next CASA volunteer training begins in August. “We are a growing CASA chapter that began in 2018,” Williams said, that the goal is serve as many children in care as possible.

A Sherrard native, he previously had worked for the Martin Luther King Center in Rock Island, and graduated from Augustana College in 2019, with a degree in psychology. Active in Quad City Music Guild, his father Bob Williams was a longtime Guild director who died last fall at 61 from a heart attack.

“I think obviously, I love the Quad-Cities, but there are a lot of service gaps that can be filled,” Williams said. “I’ve always had a passion for child welfare, for kids. My mom was a supervisor for DCFS for 30 years or so. It’s something that was always ingrained in the family. I think there are a lot of organizations that are doing a lot of great work in the Quad-Cities in terms of child welfare.”

Daniel Williams, a 2019 Augustana graduate, is advocate specialist for the CASA program in Rock Island County.

“It’s something I’ve always been passionate about and there are a lot of really cool opportunities and really great programs in the Quad-Cities,” Williams said, noting a slogan for the Child Abuse Council is “Creating Great Childhoods.”

He started his job back in March. CASA first started in Rock Island County in 2012, ran out of funding, and the current program began in 2018. There is also an Iowa CASA program, that serves families in Scott County.

One of the cool things about the program is that it aims to provide consistency for children in foster care, Williams said. “That’s a really turbulent time in their lives. They’re changing placements; they’re removed from their own home. They might be changing schools, changing caseworkers. What CASA is really meant to do is provide consistency.”

There is a low level of turnover among volunteers, who are asked to commit at least a year, he said. Some volunteers have been with the program since 2018, and in the same case the whole time.

“They are the one consistent thing for that child throughout the case, and that’s what CASA is meant to provide,” Williams said. Often, kids in the local system are placed with relatives, he noted.

“There can be turnover with caseworkers, so if caseworkers change continuously, where they might be moving different schools, different placements, and the CASA is meant to be there throughout,” he said. Each volunteer also is paired with just one case and one child at a time.

The CASA program helps the Child Abuse Council create great childhoods.

“They’re focused on that child and that case alone,” Williams said, noting caseworkers are employed by the state or contracted organizations like Bethany for Children and Families or Lutheran Social Services.

The volunteer is focused on the child, whereas the caseworker is responsible for providing the benefits and make sure the family gets what they need.

“For the CASA, it’s explicitly focused on the child. They still communicate with parties in the case,” Williams said. “They’ll be in contact with caseworkers, the foster parents, the biological parents…But it all revolves around what’s best for the child in the case.

In some cases, the CASA makes connections with other organizations or nonprofits in the community, to meet the family’s needs.

They usually do two trainings per year, starting in March and August.

“You have to be familiar with the court system, familiar with how the foster care system works,” he said. “We don’t expect any special background. We don’t expect volunteers to come in with that knowledge. So, there is a training session that goes for nine weeks, three hours a week.”

The swearing-in of the next volunteers will happen in December, Williams said. They would like to boost the program with 10 to 15 new volunteers.

The Child Abuse Council (childabuseqc.org) is based at 524 15th St., Moline.

“We’re happy that we’re able to serve 30 kids, but there’s a huge need. Right?” Williams said. “The ultimate desire is, how many kids are in foster care, we’d love to be able to have a CASA to provide for that child. The more we can grow the program, the more we can provide that benefit to those 294 children.”

Just in two months (before May 31), there was an increase of 40 kids in foster care in Rock Island County, he noted.

To get involved, you can contact Williams at danielw@childabuseqc.org or call the Child Abuse Council at 309-736-7170. Additional information about CASA can also be found at childabuseqc.org/casa.