During Pride Month, Celebrate A True Trans And Musical Pioneer

From The Weeknd to the soundtrack to “Stranger Things,” synth pop is an integral part of the musical landscape of our times, and has been for decades. Aside from minor blips when it’s faded from style, the sound of synthesizers has been a constant companion for everything from avant garde pop to boy and girl band tracks and even as one of the elements of nu metal.

However, the ubiquity of synth pop since its breakthrough explosion as part of the new British invasion of the ‘80s, not to mention its previous dancing along the edges in the ‘70s and ‘60s as part of various acts’ oeuvre, would arguably not have arrived were it not for the innovative, imaginative and ground-breaking work of a handful of early pioneers.

Robert Moog.

Delia Derbyshire.

And, of course, Wendy Carlos.

However, Carlos was not just an integral part of helping to craft the sound of the future. She was a vital figure in another way as well, as the first trans woman to openly achieve mainstream success as a modern artist.

Born in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in the decidedly non-tolerant era of 1939, she was born Walter Carlos to two working class parents. From an early age, she was a precocious musician, mastering the piano and composing her first work, “A Trio for Clarinet, Accordion, and Piano,” at age 10. However, it wasn’t only in music that she showed her brilliance. At age 14, she won an academic scholarship for building a computer and presenting it at a science fair. She was 14 at the time.

She studied physics and music at Brown University and moved to New York in the ‘60s to continue her education at Columbia University. It was there that she intertwined her twin loves of music and technology and began working with the rudimentary models of what would become the synthesizer. In 1965, at the ripe old age of 26, she worked with Leonard Bernstein to present an evening of electronic music at Philharmonic Hall.

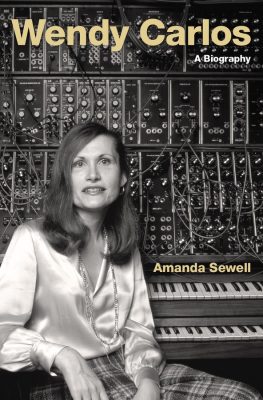

The cover to Wendy Carlos’ biography

It was during her time in New York that she met and began working with other pioneers in the early electronic music scene – Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, and a man named Robert Moog, who was developing what would become the famous Moog synthesizer. Carlos would help Moog develop the synthesizer, and began using the prototypes in her own work, which ended up on TV for commercial jingles. Her creative work remained underground, respected and well-noted, but commercially bereft of acceptance by the mainstream.

However, that would soon change.

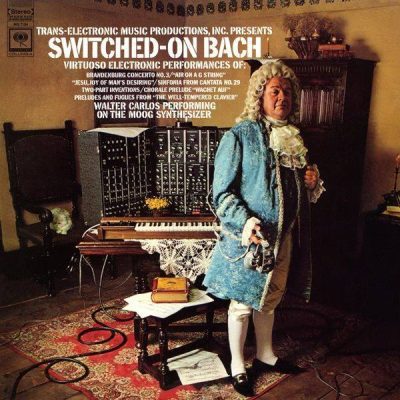

In 1967, Carlos had the idea to merge classical music composition with the new electronic format, and began noodling around with various ideas. One of those involved a reworking of various compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach. The idea, and subsequent demos, were popular with her musical contemporaries and led to a record deal with Columbia Records, where she would record them as a disc called “Switched-On Bach” in 1967.

The record took a painstaking amount of time to produce, as with primitive synthesizer technology, it had to be done one note at a time. However, the hard work paid off.

Released in 1968, the record was an instant success, and became the biggest-selling classical music album of all time.

It also became a means of salvation for its auteur.

Carlos’ “Switched On Bach” remains the best-selling classical album of all time.

Since the early ‘60s, “Walter” had been going through her reawakening into Wendy, a transformation that was extremely difficult at the time, even in a city as liberal and open as New York. She underwent extensive counseling, particularly with early transgender scientist Harry Benjamin. By 1968, she was beginning hormone replacement treatments, which began to alter her appearance, creating several uncomfortable situations for her when she was publicizing “Bach” and appearing on TV shows. However, it was that commercial success of “Bach” that also gave her the money to finally undergo sex reassignment surgery in 1972 and fully begin living her life as a woman.

However, it was not an easy transition, again, even in a time as permissive as the ‘60s and early ‘70s. Carlos recorded two sequel albums to “Bach,” both of which were released under the Walter Carlos name due to marketing reasons. She still continued to work under the masculine name for the same reason, afraid to fully make the switch.

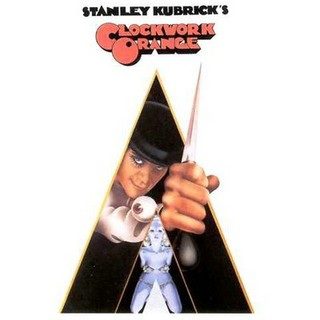

It was during that time that she recorded another massively influential album – the soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange.”

The soundtrack has been cited by countless early synth pop pioneers, from Kraftwork to Human League to Cabaret Voltaire, as being one of the most influential and impactful records in their creative genesis. It’s no exaggeration to say that soundtrack, alongside Derbyshire’s incredibly impactful “Dr. Who” theme song, are the twin blocks upon which British synth pop would be built.

Carlos would continue to have success throughout the ‘70s and early ‘80s with a variety of electronic classical albums, and would go on to work with Kubrick again on the soundtrack for “The Shining,” as well as another hugely influential soundtrack, for the movie “Tron,” in 1982.

Carlos’ soundtrack to “A Clockwork Orange” has been listed as a huge influence by bands like the Human League and Cabaret Voltaire.

In late 1978 and early 1979, Carlos would become hugely influential in another way, becoming one of the first performers to come out as openly trans, in an interview with Playboy magazine. Predictably, there was some social backlash, but none which impeded her success or creative growth. Ironically, her interviews were released just as a massive wave of musicians influenced by her sonic experimentation was gaining popularity – many of whom were also bending gender stereotypes with their androgynous images. Acts like Tubeway Army, Human League, Cabaret Voltaire, and others, mixed icy electronic sounds with ambiguous gender roleplay, creating an entirely new paradigm for pop stardom and paving the way for the takeover of British synth pop in the ‘80s. Although mentioned frequently in interviews, notably by Human League’s Philip Oakey, who was a major fan, Carlos remained under the radar even as her progenitors rose to mainstream prominence.

Still, there was something of a symbiotic relationship between them, as the rise of their androgyny and electronic sound created something of a safe space for Carlos as she transitioned in full view of the public.

“The public turned out to be amazingly tolerant, or, if you wish, indifferent,” Carlos said in an interview with Playboy in 1985, in regard to her transition. Of course, by that time, times had decidedly changed and the new teens of Gen X were far more accepting than their forebears. Openly gay and flamboyantly androgynous Boy George was an international superstar, and even more overtly cis hetero stars like Prince and Duran Duran were wearing makeup and disregarding antiquated gender tropes.

Throughout the ‘80s, Carlos continued to record, and in 1989 she won a Grammy Award for a collaboration with Weird Al Yankovic on a parody of “Peter And The Wolf.”

She remained active through the ‘90s and early 2000s, recording movie soundtracks and other instrumental works. In 2005, she re-released remastered scores for “A Clockwork Orange,” “The Shining,” and “Tron,” and a new generation of electronic musicians, from electronica stars like Daft Punk to rap and pop producers, not only listed her as a major talent and influence, but engaged in that most sincere form of modern flattery, sampling her work for new songs.

Carlos hasn’t really been active since then, but her influence as both a musician and a social iconoclast and ground-breaker in the trans community is undeniably still woven into the fabric of society. So as you see all the Pride month memorabilia, and all the events going on, as you listen to the darkwave backdrop of “Stranger Things,” realize that in so many ways, those worlds have been profoundly and positively impacted by Wendy Carlos.