“Yes, God, Yes” a Sweet, Small Film Exposing Enormity of Catholic Hypocrisy

The 70-minute teen comedy/drama “Yes, God, Yes” is a sweet, slight and mostly satisfying film that deftly, gently tackles enormous, weighty subjects – sexuality, morality, religion, personal autonomy and responsibility, and the vast, disgusting hypocrisy of the Catholic Church.

The 2019 film was written and directed by Karen Maine (who co-wrote the 2014 abortion-themed “Obvious Child”) and stars Natalia Dyer (of “Stranger Things” fame), based on Maine’s 2017 short film of the same name also starring Dyer as a shy, sympathetic, and secret rebel.

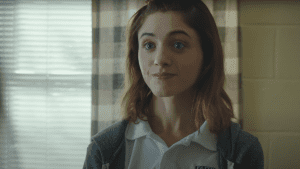

Natalia Dyer plays a teen at a Catholic Iowa high school, in a scene from “Yes, God, Yes.”

The awkward, totally identifiable feature (which does not deserve its R rating, despite the subject matter) debuted this past July in theaters and on demand, and has been available on Netflix since Oct. 22.

“Yes, God, Yes” establishes the classic high-school clash of student versus authority, but it’s no “Animal House”-level frivolity. The nature of the rebellion – a natural, hormonal awakening of sexual desire – only happens in isolation, and boy, can we identify with that nowadays as masters of our own quarantine.

In the warm-hearted story, set circa 2000 (with AOL chat rooms and primitive cell phones), Alice (Dyer) is a sexually inexperienced but curious junior at a strict Iowa co-ed Catholic high school, where Father Murphy (an upright, uptight Timothy Simons, who was Jonah in “Veep”) instructs her morality class that any sexual activity not aimed toward procreation in a heterosexual marriage is damned for all eternity.

She struggles with her feelings of desire; her curiosity in an online chat quickly attracts a gross predator, and in school Alice is the subject of a rumor that she “tossed the salad” of a classmate, Wade, at a party over the weekend. Alice denies this, admitting to not knowing what the phrase means (full disclosure: I had no idea either, and I’m in my 50s).

She and a friend decide to attend the school’s next “Kirkos” retreat – where the kids have to give up watches and cell phones (Alice falsely claims she doesn’t have a phone), and they remark how weird it is to see Father Murphy in normal clothes (like the oddity when you’re a kid

The poster for the Karen Maine film.

of seeing your teacher in the supermarket).

Alice immediately (but secretly) lusts after Chris, the sexy senior and football star who is also a retreat leader. During a hike, Alice fakes an injury so she has to be carried by him (so dreamy!) to the nurse. One night, while thinking about him, and playing on her cell phone, she accidentally discovers another use for the phone’s vibrating feature.

After her phone is discovered and confiscated, the “dirty” Alice gets cleaning duty as punishment, and when no one is around, she accesses Father Murphy’s computer, and his AOL chat to ask what “tossing salad” means, but she has to leave quickly before being found out.

To the whole group, a disappointed Murphy announces his discovery of an explicit chat on his computer, but no one claims responsibility. He later pushes Alice to confess to acting on her sexual temptations with Wade, and doesn’t believe her insistence that nothing happened.

Alice unfairly frames Wade for the earlier break-in, and while hiding to make her escape, she catches Father Murphy masturbating to a porn video saved on his computer. While alone with Chris, Alice passionately kisses him, but soon runs away, fleeing the campgrounds and comes upon a lesbian bar.

After downing a wine cooler, she and the compassionate owner, Gina, bond over how fear of damnation can warp an adolescent’s development. Gina broadens the innocent, intelligent girl’s horizons, including revealing what “tossing salad” means (Ew!).

Timothy Simons plays Father Murphy at a Catholic school retreat.

At the conclusion of the retreat, Alice tells the group, in an inspiring message we can all relate to:

“We’re all hiding stuff. All kinds of stuff. What if we just tried to be honest and to treat each other with respect? That’s what Jesus wanted, right? And then maybe we could stop feeling so guilty of who we are all the time because the truth is, we’re just trying to figure out our shit.”

Adolescence, young adulthood – and let’s face it, our whole lives – are all about just trying to figure out our shit, discover who we are, what we’re meant to be, and how we can live complete, fulfilling lives. As a parent of two adult boys, I’m no great authority figure – they often are the example for me, and I wrestle with guilt and transgressions all the time.

Natalia Dyer in a scene from “Yes, God, Yes.”

“Yes, God, Yes” is a wholesome, relatable film and refreshing in focusing on young females (as 2017’s “Lady Bird” similarly did). It fails to earn an R rating since it has very little nudity, very little profanity, and the brief online chats are fairly mild. But female masturbation? – heaven help us!!

Dyer is hardly the nastily wicked schoolgirl, but simply exploring her body, which is a natural part of anyone’s adolescence. There is nothing explicit in the film, just lightly implied. I loved seeing Donna Lynne Champlin (of “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” fame) as the strict teacher Mrs. Veda, but she was criminally under-used.

Other Catholic perspectives

As someone raised Catholic (I graduated from an all-boys Jesuit high school), and religious my whole life, I was interested to see some Catholic thoughts on “Yes, God, Yes.” You couldn’t have two more diametrically opposed views than from the Jesuit weekly magazine, America, and the Catholic News Service.

The America reviewer (a high school minister) notes that the filmmaker Maine knows of what she speaks, as an ex-Catholic herself. The review said that Catholic teens have it particularly tough (tell me about it — not having girls in school set me back immensely).

“We take the angst, awkwardness and self-consciousness that everyone feels in adolescence and combine it with Catholic Guilt, that unshakeable sense that no matter what you do, you are letting God down,” the review says. “At a time when you already feel like you’re doing everything wrong, you also become aware of eternal damnation.”

America is a national weekly magazine published by the Jesuits in the United States.

He wrote the film is “less interested in skewering the retreat or Catholicism than it is with the hypocrisy of religious authorities. (Ironically, this puts the film in continuity with the Gospels.) Throughout the film, Alice realizes that several people who have claimed moral authority—including cool senior leader Nina (Alisha Boe of ‘13 Reasons Why’) and Father Murphy himself—are also deeply fallible and hold themselves to a less rigorous standard.

“This hypocrisy undermines the authority of leaders and drives people, like Alice, away from the faith; the film does not touch directly on clerical sexual abuse, but it lurks in the subtext,” the review says.

The new film could serve as a cautionary tale.

“We should approach young people with care and the humility to listen to their questions while authentically sharing, and modeling, Catholic teaching,” the America review said. “Our goal should always be to help them say ‘yes’ to God, not to command blind obedience.”

Karen Maine – who went to high school in Des Moines and is married to a Jewish man – told iowastatedaily.com in July:

“I just hope young women see and recognize something about themselves in it that allows them to feel less guilty or awkward or shameful about feeling sexual or having sexual experiences or just wanting to explore their body. I think what’s really interesting about even the way probably public schools teach sex ed is it’s mostly focused on reproduction, which doesn’t involve female pleasure at all.”

Meanwhile, the more conservative CNS will pretty much have none of this forgiveness and grace crap.

Their reviewer does at least credit Dyer for a “gift for eliciting sympathy and the script carries a worthwhile message about the harm done by gossip.” Yet that’s apparently “entirely overshadowed by the massive chip on Maine’s shoulder and by the moral that the best way to overcome sins of the flesh is to stop calling them sins.”

“Nor is it only carnal transgressions that are overlooked,” the review said. “Alice frames Wade for something she’s done wrong — with serious consequences for the way he’s regarded by adults and his peers alike — and experience no remorse for having done so. Bearing false witness, it seems, is all part of growing up and achieving liberation.” I agree Alice should have fessed up to using the priest’s computer, but also called out his transgression.

CNS claims the film “contains anti-Catholicism, strong sexual content, including aberrant behavior and images of upper female nudity, a couple of mild oaths and a few uses of crude language. The Catholic News Service classification is O — morally offensive.”

That nearly knocked me out of my chair – this film is morally offensive. O, really?????

Little moral authority left

That swipe really, really made me mad. As any religion should teach that we all are fallible, human, and in constant need of self-improvement, the Catholic Church itself has consistently and for centuries failed to apply those lessons. How dare you call an honest, humane, simple film like this “morally offensive”?

Want to talk about morally offensive? Look in the damn mirror. What hypocrites – how dare they claim the moral authority to tell how any of us how to live?

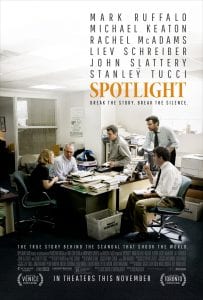

The 2015 film “Spotlight” highlights the Boston Globe’s Pulitzer-winning investigation into the church sex-abuse scandal.

If you haven’t seen the Oscar-winning 2015 film “Spotlight,” centering on the Boston church sex-abuse scandal, see it right away. (It’s currently also on Netflix.)

Tom McCarthy – a close friend and Boston College classmate of one of my brothers – directed and co-wrote the amazing, brave film, which fittingly is an “All the President’s Men” for our time, a dogged, determined newspaper taking on the powerful and forcing them to be accountable.

“Spotlight” shed light on the Boston Globe’s 2001 investigation into the decades-long priest sex-abuse scandal and the Catholic Church’s attempt to cover it up. The movie (which stars Michael Keaton, Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams and John Slattery) won the 2016 Academy Award for Best Picture, along with Best Original Screenplay, from six total nominations.

McCarthy also grew up Catholic, and I got to speak with him in 2015 for a Dispatch/Argus feature. His reaction to the crisis?

“It was disgusting, frustrating, infuriating. It’s so inconceivable that an institution that’s so iconic, to allow this to exist, that was very upsetting,” McCarthy said. It was little known in the ’80s, because no one was coming forward to publicly accuse priests, who were often transferred, parish to parish, to avoid any punishment.

When Martin Baron arrived as Globe editor (played by Liev Schreiber in the film), the paper focused more on the church cover-up of clergy sexual abuse. “Cardinal Law had knowledge about the abuse, and did nothing,” McCarthy said of Bernard Law, who resigned in December 2002 as Archbishop of Boston amid the controversy.

In 2003, he was castigated by the Massachusetts attorney general, who said that as many as 1,000 children had been sexually abused by 250

Writer-director Tom McCarthy (center), at the New York premiere of “Spotlight” Oct. 27, 2015, with Michael Keaton (left), and Walter Robinson, former Boston Globe reporter and editor who led the coverage of the Catholic clergy sex abuse scandal, and for which he personally accepted the 2003 Pulitzer Prize on behalf of the paper. (Photo credit: Marion Curtis/Startraksphoto.com)

priests in the Boston archdiocese over 40 years, and that Cardinal Law had known of the problem even before he arrived in 1984 and had tried to suppress any publicity about it to save the church from disgrace.

The cardinal, was appointed in 2004 as high priest of one of Rome’s four most prestigious churches, and died in 2017. The New York Times wrote that for years in Rome late in life, he was “a kingmaker of American bishops, serving on the Vatican committee charged with advising the pope on bishops’ assignments. In this position, he helped shape the American church’s hierarchy for a generation. Many of his favored candidates are still leading American dioceses.”

“The church in 2001 wanted to paint the crisis as a few bad apples,” McCarthy said. “The (Spotlight) investigation made clear this was a systemic problem for years that the cardinal knew about.” The Globe “helped people see this was in fact a crisis of massive proportions,” he said.

Want to talk about morally offensive?

In December 2007, the Catholic Diocese of Davenport reached a $37-million settlement to compensate victims of sexual abuse by clergy and let the diocese emerge from bankruptcy that it declared in 2006. The money was to be divided among 156 people who say they suffered abuse by priests and lower-level employees dating from the late 1930s.

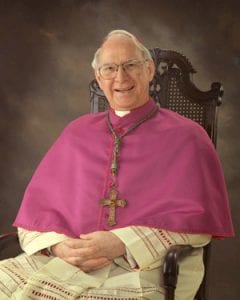

According to bishop-accountability.org, in February 2004, Bishop William E. Franklin issued a report on the Davenport crisis, and his

Bishop William Franklin headed the Davenport Diocese from 1994 to 2006.

“transparency and openness” were hailed as a positive development. “But a close analysis reveals many apparent errors and omissions in the bishop’s account,” the site says. “What do these problems say about the diocese’s management of the abusers in its midst? And in light of the questions we raise, how is the diocese likely to approach the rigors of bankruptcy and the jury trials that will surely come?”

At that press conference in 2004, the Davenport bishop told victims: “I am sorry for any pain, agony and suffering caused by any action of any priest you trusted and wanted to trust. Whatever happened should never have happened. It was not your fault. I also humbly apologize for any shortcomings and misunderstandings that may have occurred when some of you came forward to report abuse. I ask God to give all of us the compassion, the wisdom and the energy to live and to treat all as his beloved children.

“I hope this information presented will be a sign of our effort in the Diocese to provide help in ongoing recovery. I also hope that the actions we are taking will be a sign of our commitment to the policy that no priest or deacon of the Diocese of Davenport will remain in public ministry if there is reasonable cause to believe that the priest or deacon abused a minor at any time.”

Want to talk about morally offensive?

Bishops and other leaders of the Catholic Church in Pennsylvania covered up child sexual abuse by more than 300 priests over a period of 70 years, persuading victims not to report the abuse and law enforcement not to investigate it, according to a searing report issued by a grand jury in 2018.

The report, which covered six of the state’s eight Catholic dioceses and found more than 1,000 identifiable victims, is the broadest examination yet by a government agency in the U.S. of child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. The report said there are likely thousands more victims whose records were lost or who were too afraid to come forward.

Bernard Law was Archbishop of Boston from 1984 to December 2002, when he resigned over the diocese sex-abuse scandal. (Photo credit: City of Boston Archives)

It catalogs horrific instances of abuse: a priest who raped a young girl in the hospital after she had her tonsils out; a victim tied up and whipped with leather straps by a priest; and another priest who was allowed to stay in ministry after impregnating a young girl and arranging for her to have an abortion.

But “Yes, God, Yes” is offensive?

The sexual abuse scandal has shaken the Catholic Church for more than 15 years, ever since explosive allegations emerged out of Boston in 2002. But even after paying billions of dollars in settlements and adding new prevention programs, the church has been dogged by a scandal that is now reaching its highest ranks, the New York Times said. The Pennsylvania report came soon after the resignation of Cardinal Theodore E. McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington, who was accused of sexually abusing young priests and seminarians, as well as minors.

McCarrick, now 90, resigned in July 2018, which was accepted by Pope Francis. After a church investigation and trial, he was found guilty of sexual crimes against adults and minors and abuse of power. McCarrick was dismissed from the clergy in February 2019. He is the most senior church official in modern times to be laicized and is believed to be the first cardinal ever laicized for sexual abuse.

Do you think the church scandal was limited to the U.S.? Hardly.

Just take a look at the list of end credits from “Spotlight,” which shows dozens of dioceses around the world where major sex-abuse cases were uncovered. It’s staggeringly sickening.

I could go on, but it’s exhausting. For all the church’s sanctimony about preserving life, they’re also a bit hypocritical during this crisis of Covid-19. I am the piano accompanist for Zion Lutheran Church in Davenport and we haven’t had an indoor service in person since mid-March.

Yet the Diocese of Davenport has allowed indoor Mass to continue since June 22.

Bishop Thomas Zinkula announced then that everyone must wear face protection. Initially, seating was limited to every third pew and horizontally six feet apart from other households, in order to maintain safe distancing.

Distancing should also be maintained while gathering, during the Communion procession (Communion during Covid, really?), and following Mass. Singing is omitted for the time being to reduce airborne pathogens. Those who are at a greater risk of infection due to age and/or health condition should stay home. Throughout this pandemic, all Catholics in the Diocese of Davenport are dispensed from the obligation to attend Sunday Mass.

Throughout the nation, the two days with the most number of Covid cases on a single day (in the whole pandemic), were last Friday and Saturday. Now, 8.7 million Americans have been infected with the coronavirus and at least 225,100 have died. But let them come to church inside every week, especially as cases hit all-time highs? Sure, why not?

Those of us who are staying home should be treated with mercy and compassion. And like Alice in “Yes, God, Yes,” if one of the few forms of entertainment when we’re alone is self-pleasure, what the hell is wrong with that?

Unlike all those priests, we’re not hurting anyone else. Our body’s a temple, right? If we can’t go to church, at least it’s another divine form of worship, which deserves a hand.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.