Quad-Cities Mourns Death of Former Silvis Leader Joe Terronez

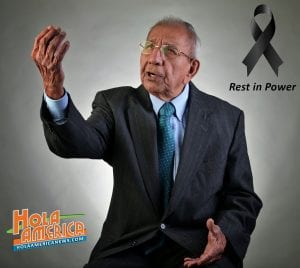

Many in the Quad-Cities today are mourning the death Saturday night of Joe Terronez, 91, a former longtime leader of Silvis and passionate advocate of the area’s Hispanic heritage.

“He showed us that change does not come willingly, that we have to persevere to right some of the injustices in this world,” Tar Macias, publisher of Hola America News, posted on Facebook Sunday morning.

“Thank you Mr. Terronez for your leadership, your strong spirit and I am most grateful for your kindness to me all these years. We have lost a giant,” Macias wrote. “Rest in Power dear friend.”

Former Silvis mayor Joe Terronez died Jan. 2, 2021 at age 91.

Sonya Jasso of Silvis posted:

“You will always be remembered and loved by so many for your courage and your dedication to fight for equality for your Latino people. Thank You so much for your hard work and dedication and helping the poor. We on earth will follow your example to have love and compassion for all people.”

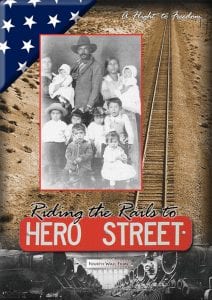

Moline-based filmmaker Tammy Rundle, who featured Terronez in the Fourth Wall documentary, “Riding the Rails to Hero Street,” posted:

“Our hearts are very heavy over the loss of Joe and our deep sympathy goes out to all who loved him. What an incredible legacy he has left. And what an honor to have known him.”

Terronez’s father moved to the Q-C from Mexico at age 13, and was a blacksmith for the railroad. Joe was born in boxcar No. 4 in the Silvis Yards on Feb. 15, 1929. He married Rebecca Herrera on Nov. 6, 1948. She passed away Nov. 19, 2018. They were married for 70 years.

He retired from International Harvester in 1984.

Terronez became one of the first Hispanic city council members in the state in the early 1960s.

The landscape changed politically and ethnically, he said, with more minority representation. One generation, his father’s, provided opportunities for the next, his own. Joe Terronez tried to provide his eight children with opportunities, he said in a 2011 Dispatch/Argus interview.

The retired Case IH assembler and combine repair man said that’s the natural progression of a successful community, regardless of race, creed or color. With the 2010 census, the Q-C Hispanic population grew nearly 34 percent over that past decade.

“Things have changed,” Terronez said then. “I saw it. I look back at the way things were. It was hard for a Mexican to be sitting in their group (city government). You know, elected like them. It was hard.

Terronez was interviewed for the Fourth Wall Films’ documentary, “Riding the Rails to Hero Street.”

“I think there has been some great strides for good, but they’ve (Hispanics) got quite a bit to go. A lot of Hispanics are coming in. They need help. I think if the jobs open up, it will help out a lot.

“They’re good workers, hungry. You give them a job, they’ll work it. That’s it in a nutshell.”

Marc Wilson, author of “Hero Street U.S.A.,” wrote in a Sept. 22, 2020 profile for Hola America, that Terronez was a champion for the recognition of Silvis’ 2nd Street as Hero Street – to honor the eight men who lived on the street and were killed in World War II and the Korean War.

In the early ‘60s, the street was largely ignored, even though eight Mexican-American soldiers from 2nd Street – Tony Pompa, Frank Sandoval, Willie Sandoval, Claro Solis, Peter Masias, Joseph Sandoval, Joseph Gomez and Johnny Muños – had died in combat in World War II and Korea. “No one disputed that the eight deaths is the most of any single block in America,” Wilson wrote.

But for the first decades after the wars ended, no one seemed to care much, except for family members and close friends who mourned the heroes’ deaths all the days of their lives.

Resurrecting Hero Street

In 1963 (when Joe Terronez first joined the Silvis City Council), the ramshackle homes on what is now Hero Street had no city sewers and limited access to public water. Amazingly, it was the only block in Silvis that wasn’t paved, Wilson wrote.

“When it rained, the street turned to quicksand. You just sank into it,” Terronez said in September.

The mud sometimes was so bad that when the heroes’ bodies – those that could be found — were returned for wakes in their families’ homes, the caskets had to be carried up the street by hand — the street was too muddy for a hearse’s weight, Wilson wrote.

Discrimination showed its ugly head in other ways than an unpaved street and no sewer lines.

The 90 or so Mexican-Americans veterans who returned to the neighborhood from service after World War II and Korea were blackballed — denied membership in the Silvis chapter of the VFW. They had to form their own VFW chapter, Post 8890 in nearby East Moline (which survives today after the Silvis VFW closed for lack of members.)

The poster for the 2019 “Riding the Rails to Hero Street.”

Into this breach of discrimination and poverty stepped the then 34-year-old Terronez.

He was one of 17 children born to immigrant parents who had fled the chaos of the Mexican Revolution. His father worked as a blacksmith at the Rock Island rail yard in Silvis. The huge family lived many years in a boxcar in the rail yard before moving to a small house on 4th Street.

Joe, born Feb. 15, 1929, was perhaps the last person born in the boxcar settlement in the rail yard, Wilson said. Later in the year he was born, the Mexicans moved from their boxcar settlements into small houses on 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Streets in Silvis. Some of the Mexicans – too poor to build, buy or rent a house — lived in boxcars they dragged from the rail yard.

Joe says his family was one of the luckier ones. “My Dad always worked – he was a great black smith – and never went hungry, and even during the Great Depression no one who came to our door went away hungry. My Dad remembered that in Mexico he had to beg for food. He knew what true hunger was like, and neither he nor my mother would let anyone go away hungry. The hobos from the rail yard knew where to find us, where to find something to eat.”

Joe said he decided early on that he wanted to be successful. “While my brothers and friends were out playing, I was studying. If the teacher assigned three or four pages for us to read, I read 20 or 30 pages. Pretty soon, I had the whole book read. I wanted to know how things worked, and I read anything I could put my hands on. My Dad would see me studying all the time and nod his head and tell me ‘you’re going to be somebody.’ And I knew he was proud of me.”

After graduating from East Moline High in 1948, Joe went to work at the assembly line at the nearby International Harvester plant. He became active in the United Auto Workers union, rose to steward before being elected to the full-time job as grievance arbitrator.

In Wilson’s 2009 book on Hero Street, he quoted Terronez as saying: “I learned a lot from the union. I learned how to be tough and not get pushed around. I learned that you’d better not let your own people get away with things, because all of us would get hurt. Mostly, I learned how to get things done the right way, and that I didn’t have to take nothing from nobody, if it wasn’t right.”

He got involved in politics. He and his great friend Nick Trujillo studied immigration and election laws, and helped the Mexican-American residents of Silvis 1st Ward (2nd Street to 7th Street) to become naturalized U.S. citizens, and registered voters. “We wanted to do things right – through the system.”

Helping lift people out of poverty

The newly enfranchised voters helped him win a seat on the city council, and one of his first missions was to help the impoverished residents of 2nd Street. He faced open hostility when he showed up at City Hall, but “I didn’t care if they liked me, so long as they respected me and treated my people right,” Wilson wrote.

He quickly gained respect by out-working all the other aldermen – by attending every council meeting, committee hearing, and public event, and by reading every word of every document the council needed to review.

His first successes included getting improved water and sewer services for 2nd Street. But in 1965 he ran into his first great battle.

The city won voter approval to issue bonds to repair, repave and pave city streets. But the city council decided to leave 2nd Street unpaved.

“They (the other city officials) said the houses (on 2nd Street) were built all over the place, and on the right-of-way, so there was no real

The cover of Marc Wilson’s “Hero Street U.S.A.”

street there, and no way to get a straight street that could be paved,” Terronez said.

The city ran out of money before 3rd Street was paved. “I screamed discrimination out loud,” Terronez said, and the city found enough money to pave 3rd Street.

But it was a hallow victory — 2nd Street – the home of the eight men who’d paid the ultimate sacrifice – was left unpaved to Terronez’s consternation.

Terronez, VFW Post 8890, the local chapter of the American GI Forum, Moline Dispatch reporter Vi Murphy, and many others took up the cause of remembering the heroes of 2nd Street. They led an effort to rename 2nd Street as Hero Street U.S.A.

In 1967, the city council approved Terronez’s motion to rename the street, and the U.S. Postal Service also agreed to the name change to Hero Street. But still the street – grand name and all – remained unpaved.

Terronez and Jesse Perez, head of the local American GI Forum, recruited a heavyweight to help them. Vincent Ximenes – President Johnson’s chief of the Equal Opportunity Commission and a senior official in the American GI Forum – accepted their invitation to visit Silvis.

Ximenes, who won the Distinguished Flying Cross during 50 combat mission in World War II, had grown up in a poor Mexican-American village in southern Texas. He visited the residents of 2nd Street, and heard their stories of their lost hijos.

Ximenes returned to Washington and arranged for $44,450 federal matching grant to help fund a park on Hero Street. But the city council voted 6-1 against the park, with Joe casting the lone yes vote.

Ximenes sent the Silvis mayor a message – if you don’t match the grant and build the park on Hero Street, the city would lose other federal funds. So, the city council voted again, and the park won by a 5-2 vote. Terronez helped arrange in-kind donations of labor and materials – much of it from John Deere Co. – to build the park.

Ximenes came from Washington on Memorial Day 1969 to dedicate the park. He said: “If they died for democracy, (these eight heroes) did not die so that darker Americans would continue to face barriers in education and employment…They did not die so that thousands of Americans, brown, black, yellow or white, should suffer the pangs of starvation and malnutrition…They did not die so that Mexican-Americans, Negroes, and American Indians should fail to receive acknowledgement of a job well-done…”

But still the street was unpaved, Wilson noted.

“At first,” Terronez said, city officials “used the old excuse that there wasn’t a proper right-of-way, and not enough setbacks” for a paved road. “But we told them we’ll have people from all over the county coming to see Hero Street Memorial Park, and it would be embarrassing to the city and its residents if the street wasn’t paved. So they finally agreed to pave it.”

The first Hispanic mayor in Illinois

Terronez went on to serve 28 years on the Silvis City Council, including the last four years as mayor – the first Hispanic mayor in Illinois.

He outworked everyone else, and almost never missing a council session, hearing, or committee meeting, Wilson wrote, noting he read all the fine print. He says he knows where every sewer and water line is buried in Silvis – plus most of the political skeletons in Rock Island County.

He and his wife, Rebecca, raised eight children. They lived for many years on 3rd Street in a house that Joe built. In 1969, Joe was honored in Chicago with the National Hispanic Hero Award by the U.S. Hispanic Leadership Council. On Labor Day of 2014, the Democratic Party of Rock Island County honored him for his lifetime commitments and achievements.

“Riding the Rails to Hero Street,” the first film in the Fourth Wall Hero Street documentary series, tells the story of the immigrants’ early 1900s journey from Mexico, during the revolution, to Cook’s Point in Davenport, Holy City in Bettendorf, Iowa, and the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad train yards and boxcar homes in Silvis.

The families of Hero Street experienced both acceptance and discrimination in their new community. Around the time of the Great Depression, the families were removed from the rail yards and some moved box cars or built new homes on 2nd Street in Silvis.

Interviews with family members, friends, veterans, community leaders and historians are combined with vintage photos, film, and archival materials to tell an unforgettable story of American courage, character and perseverance.

Only a block and a half long, the street lost six young men in World War II and two in the Korean War, more than any other street in America. Hero Street has provided over 100 service members since World War II.

Joe Terronez attended the premiere of “Riding the Rails to Hero Street” and “A Bridge Too Far From Hero Street” (William Sandoval’s story) on Veterans Day eve, Nov. 10, 2019 at the Putnam National Geographic Giant Screen Theater to a sold-out crowd. And Joe was part of the Q&A following the showing.

When University of Oklahoma Press released Wilson’s Hero Street book, it wrote:

“As debate swirls around the place of Mexican immigrants in contemporary American society, this book shows the price of citizenship willingly paid by the sons of earlier refugees. With Hero Street, U.S.A., Marc Wilson not only makes an important contribution to military and social history but also acknowledges the efforts of the heroes of Second Street to realize the American dream.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.