New Harriet Beecher Stowe Documentary From Quad-Cities Filmmakers to Screen on Feb. 18

Saturday In The Arts is a comprehensive weekly feature looking at a trend, personality, or major subject involving the Quad-Cities arts and entertainment scene.

Harriet Beecher Stowe was a small, quiet woman who wielded a towering, thunderous literary voice that helped change the conscience and course of a nation.

Barely five feet tall, Stowe (1811-1896) is just 23 in the award-winning docudrama “Sons & Daughters of Thunder (2019) by Moline-based filmmakers Kelly and Tammy Rundle of Fourth Wall Films.

A half-hour companion documentary, “Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe,” premiered last February on WQPT-PBS, and will be presented online by the Bettendorf Public Library on Thursday, Feb. 18 at 2 p.m., in honor of Black History Month.

A Q&A with the film producers and Christina Hartlieb (executive director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati, Ohio) will follow the film via Fourth Wall Films’ Facebook page at www.facebook.com/Fourth-Wall-Films-173844695995934.

Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe tells the little-known story of the famous writer’s life in Cincinnati, and how those life-changing experiences contributed to her best-selling novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (1852). Stowe lived in Cincinnati between 1832 and 1850, and just after her move to Maine, she adapted her moving observations and anti-slavery sentiment into America’s most influential novel.

The poster for “Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe.”

The documentary features writers, historians and storytellers — including Joan Hedrick, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life.”

“The Cincinnati years, I think, profoundly affected her,” Hedrick says in the new film. “Her early marriage, her early motherhood – I think it was hard for her to leave that sacred ground. When she moved there, she was a New Englander, but when she went back East 18 years later, she was an American.”

The 1834 Lane Seminary debates on slavery (the focus of the “Thunder” film) and Stowe’s time in Cincinnati are not well-known nationally, Hartlieb said recently.

“Harriet Beecher Stowe is probably the most underrated author ever,” she said. “What she was able to accomplish was that she changed public opinion on the issue of slavery. Before ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’ people in the North were not abolitionists. They were pretty indifferent – that slavery thing? That’s down in the South. Why should I worry about it?

“After reading ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’ that’s when people start to go, that slavery thing is really bad, I had no idea people were treated that way. I had no idea that was going on,” Hartlieb said. “The reason that this white woman who grew up in New England was able to do that was the 18 years she spent in Cincinnati, and the people she met here, and the issues she was exposed to.”

Stowe’s Cincinnati years had never been a focus of a previous book or documentary, Kelly Rundle said recently, noting Hedrick’s 1994 biography addresses the period as part of a comprehensive look at Harriet’s action-packed life.

“I think what we’ve done is unique in terms of a narrative film, certainly, and unique for a documentary,” he said. “So it’ll be a story that most people have not heard. If they know something about Harriet, chances are they don’t know this story. A lot of people in Cincinnati don’t know it, still. They don’t know the house is there.”

The DVD cover for “Sons & Daughters of Thunder.”

A few clips from the Emmy-nominated docudrama Sons & Daughters of Thunder are included in the “Becoming” documentary and feature acclaimed actors, including Jessica Taylor of Davenport as a young Harriet Beecher and husband Tom as abolitionist Theodore Weld. Dee Canfield of Moline is the voice of elder Harriet in the documentary, reading excerpts from a handful of her letters (beginning at age 15).

A number of historical sites appear in the film, including the Harriet Beecher Stowe House and John Rankin House in Cincinnati.

The doc includes interviews with Philip McFarland, author of “The Loves of Harriet Beecher Stowe”; historians Chris DeSimio, Christine Anderson, Ph.D., John E. Douglass, Ph.D.; John Getz, Ph.D., and Michelle Watts, Ph.D.

Production took place in Cincinnati, Piqua and Ripley, Ohio; Maysville, Ky.; Litchfield and Hartford, Conn.; Brunswick, Maine and Andover, Mass. The project got a major grant from Ohio Humanities (an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities), and Friends of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House served as the fiscal sponsor for the grant.

From Connecticut to the “West”

Harriet was born in Litchfield, Conn., on the site of what became the nation’s first law school and education was highly prized. Her mother died when she was 5, and her father, Lyman Beecher (1775-1863) was the most famous clergyman of the pre-Civil War period, the doc says.

He was a Presbyterian minister, co-founder and leader of the American Temperance Society, and the father of 13 children (over two

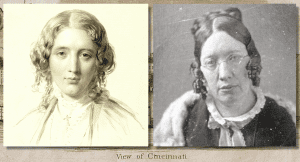

Harriet and her father, Lyman Beecher.

marriages; first wife died in 1816). After graduating from Yale and beginning his career as a pastor, Beecher moved to Cincinnati to act as president for the Lane Seminary; a role which he had from 1832-1852.

During his time at the Seminary, Beecher was a professor of theology, as well as pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church of Cincinnati.

In 1829, Harriet was part of a letter-writing campaign against removal of the Cherokee Indians. In 1832, Lyman Beecher moved his family to Cincinnati, to become president of Lane Theological Seminary. Religion played a huge role in society then.

Lane Seminary was founded in 1829. After the slavery controversy, the school suffered from financial difficulties and Beecher was forced to lease campus land to private homeowners. In 1932, Lane Seminary became part of the McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. In the years that followed, evidence of the campus slowly began to disappear.

Then part of the American West, Cincinnati was viewed as an exotic, exciting place, where they could have an effect, the film says, noting Cincinnati was an important city to the country, and the population was booming — more than doubling every decade since 1800.

The city was divided from Kentucky (a slave state) by the Ohio River, and Cincinnati’s population was diverse, including home to a huge pig population, and bore the nickname “Porkopolis.”

“For Stowe, I think it was extraordinarily stimulating,” Hedrick said of Cincinnati, a southern North city – slavery ended where Ohio began.

Harriet became a worldwide celebrity after the 1852 publication of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

The whole Beecher family was involved in social reform, and Harriet was a member of the “Semi-Colon Club,” the premier literary social club in Cincinnati, which met every Monday night. She was very well-educated for women at the time, the doc says. They all wrote pieces, and she didn’t write about the West or slavery, but about New England.

“In that setting, she developed a very intimate narrative voice, which is a hallmark of much of her fiction,” Hedrick says in the film. Harriet met Salmon Chase, a U.S. Senator who became Ohio governor, was an ardent abolitionist and eventually became sixth Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 1829, Stowe heard of race riots in Cincinnati. With fellow teachers, they went to nearby Washington, Ky., a large town. Harriet witnessed a slave auction, where a child was sold away from its mother. She was just stunned and absorbed everything.

“She had this gift for keeping things inside her for a long time, before she’d commit them to paper,” Chris DeSimio says in the film.

The Rankin House was home to abolitionist and Presbyterian minister John Rankin, his wife Jean, and their 13 children. Part of the Underground Railroad (a network of secret routes and safe houses where slaves sought escape and freedom), it’s estimated that over 2,000 fleeing slaves stayed with the Rankins, sometimes as many as 12 at a time. Though slavery was illegal in Ohio, slaves could still be apprehended due to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, which legally compelled Northerners to return runaway slaves, infuriated Stowe and many in the North.

Death and new life with Calvin Stowe

In addition to the horror of slavery, the Beecher family and the city were affected by the brutal, relentless cholera epidemic at the time (spread by dirty water). Harriet was best friends with Eliza Stowe, the wife of Biblical scholar and Lane teacher Calvin Stowe. Eliza died from cholera in summer 1834 in her mid-20s.

Moline filmmakers Tammy and Kelly Rundle.

That year also was pivotal at Lane, where the first U.S. public debates about the possible abolition of slavery took place.

In my March 2019 review of “Sons & Daughters of Thunder” (for the Dispatch/Argus), I wrote:

As a 1986 graduate of Oberlin College in Ohio, I’ve admired the fact that the private, liberal-arts school (founded in 1833) was one of the first to admit women and African-Americans. But I never knew its first president — Asa Mahan, a Congregational minister — was among the little-known “Lane rebels,” who left Cincinnati’s Lane Theological Seminary after the school sought to crush their call for slavery’s abolition.

This fascinating, inspiring slice of influential U.S. history is told with characteristic grace, intelligence and emotional power by Moline-based Fourth Wall Films in its first narrative docudrama, “Sons & Daughters of Thunder.” The stirring 85-minute film premiered last weekend at the Putnam Giant Screen Theater, attended by 432 people in two screenings, each followed by a talk with filmmakers Kelly and Tammy Rundle, and key cast members.

Seeing the beautiful finished product, and hearing from those involved, it clearly was a labor of love. It’s been about a 10-year process, since the Rundles first heard about the 1970s play of the same name by Earlene Hawley and Curtis Heeter. It chronicles the beginning of the end of slavery in America with the first public debates on slavery, in 1834 — 29 years before President Lincoln issued his landmark Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves.

The patiently paced film, which gathers in dramatic force as it unspools, stars real-life married couple Jessica Taylor as author Harriet

Jessica Taylor as a 23-year-old Harriet Beecher in “Sons & Daughters of Thunder.”

Beecher, then 23 (whose father Lyman was Lane president), and Tom Taylor as abolitionist Theodore Weld, a founder of the seminary who attended as a student and led the anti-slavery call. Harriet met Lane professor Calvin Stowe in Cincinnati (in the film played by Dan Rairdin-Hale), whom she married in 1836.

Students at Lane debated slavery, and abolitionists attacked colonization (which was supported by Lyman Beecher), because in their mind, it was a scheme to encourage all people of color to go back to Africa, back to where they came from.

The debates took place over 18 nights in February 1834, including children of slaveholders, telling what slavery did to them and slaves themselves. The most dramatic testimony was given by a former slave, James Bradley, who wanted to be a minister, and enrolled at Lane Seminary.

They voted against slavery, the trustees of the college were outraged against this radical activity, and they shut down all speech about slavery. The students were outraged. Theodore Weld, a prominent abolitionist and leader of the cause, led a walkout of the students to Oberlin College, 218 miles northeast.

Harriet saw her father’s dream shattered by the students’ exodus, which left just five students left at Lane (and two of them were her brothers).

The Beecher home in Cincinnati as seen in the Rundles’ documentary.

After grieving over his wife’s death, Harriet comforted Calvin, and they married in 1836. At the time, she was 25, thought to be very late to marry then (women of that age were called “a spinster,” the film says).

Hedrick notes her sister Catharine (played by Kim Kurtenbach in “Thunder”) never married, so it was a surprise that Harriet married. She and Calvin were perfectly matched intellectually, but were different personally speaking.

They had six children in Cincinnati, and employed servants at home. She was able to carve out time for herself to write. Calvin encouraged Harriet to write more and was very supportive of her career, Hedrick said.

After 1836 riots in Cincinnati, Harriet was outraged, and wrote a letter to the editor under a male pseudonym. A woman employed in her house, a fugitive slave, was sought by her master, and Calvin and Harriet arranged for her to escape in the middle of the night.

Another death and turning point

In 1849, cholera again swept through the city, and Harriet’s youngest child (Samuel Charles), contracted the disease at 18 months and quickly perished. Losing him made her understand what a slave woman felt when a child was taken away.

“The turning point in Stowe’s personal and literary life came in 1849, when her son died in a cholera epidemic that claimed nearly 3,000 lives in her region,” according to womenshistory.org. “She later said that the loss of her child inspired great empathy for enslaved mothers who had their children sold away from them.”

“She was with him for every moment of his last breathing minutes of life,” Tammy Rundle said of Samuel. “It was a devastating thing for her

Harriet Beecher, left, and her older sister Catharine, who were both teachers.

to go through, and I think that probably is the most powerful part of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ – because she was able to use that experience and reach into the hearts of those who were reading.”

“Her skill was taking these contemporary issues, that were divisive, and turning them into drama,” Kelly said, noting Stowe appealed to people’s hearts. “It sounds weird now, but people suddenly realized that slaves were human beings and that they had feelings; they had families and we shouldn’t be enslaving them.”

Harriet was very disciplined about writing, struggling to find the time and energy to write, against the demands of children.

“She loved being a mother very much and she loved gardening,” Tammy said.

“I sometimes wonder if she were here, what she would be thinking right now, of everything that’s happening,” she said of current racial strife and divisive politics.

Going through the current pandemic has made the 19th-century cholera epidemic easier to understand, Kelly said. “They had even less

Harriet Beecher Stowe stood just under 5 feet tall.

knowledge of what was causing it, so they didn’t have things they could do.”

“This business of slavery was so horribly divisive, beyond anything we’ve ever experienced,” he added.

“She’s not an extroverted person, but she is someone who wants to make people see what she sees,” Hartlieb said of Harriet. “I often point to one of her earlier pieces, her first political piece of writing, which took place in 1836, during multiple race riots in Cincinnati.”

Harriet watched that go on, and wrote a letter to the editor, set up like a short story of two men talking at the dinner table. One argument is freedom of the speech is important and if you don’t agree with someone, that’s no reason to beat them up in the street, Harriet wrote. “When you start that kind of violence, it’s probably going to backfire on you,” Hartlieb said. “These are the things Harriet is saying in 1836 and she’s like, wake up people! You can’t be doing this and that’s something we can still listen to today.”

In “Thunder,” Harriet is at the debates and speaks, but Kelly Rundle doesn’t think that ever happened in real life. “We know she didn’t write about it and there’s no record of it,” he said. “This was such a big event and it’s hard to describe the effect it had on Cincinnati.”

“The history is just filled with these violent uprisings,” he said. “The debates did not cause a riot, but it was on the verge of causing a riot. Harriet would have been aware of all of that. We know from her writings later that she admired Weld’s work and his writings, and was inspired by them.”

“We don’t know exactly when she changed to more of an abolitionist,” Tammy said.

DeSimio said she internalized things — when she was in Cincinnati early on, she wrote about the East Coast, and after she left Cincinnati, she distilled that experience into “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

“Maybe it’s like a lot of things; you want to get some distance on it before you dive in,” Kelly said. “Maybe it even helped to be away from the city, to write that book.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) began and ended her life in Connecticut.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 really pushed Harriet over the top, Tammy said.

“Not only was it not legal then to help someone escape, but a slave owner could come to your house and impress you into service to help him capture a slave,” Kelly said. “It didn’t settle well with a lot of people in the North.”

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin” really tipped the scales nationally toward abolition, he said.

“We were more interested in the experiences that brought that about – that transformation,” Tammy said.

“I would argue that without Cincinnati, without the Cincinnati years, you don’t have ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ and you have a different American history,” Kelly said. “You don’t have that wave of public sentiment that took place when her book was published. It wasn’t even just the book; people adapted it for the stage.”

“More people saw the play than read the book,” he said. “Now, if a movie becomes so popular that everyone’s talking about it or wants to see it, it was that kind of a sensation, but with a book, a novel.”

Creating a worldwide sensation

When Stowe and her family left Cincinnati in 1850, she was pregnant with her seventh child. That year, Calvin Stowe joined the faculty of his alma mater, Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine. The Stowe family lived in Brunswick until 1853.

Harriet first penned “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” as 41 weekly installments in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era between June 5, 1851 and April 1, 1852, and was met with hostility by slavery proponents, according to the National Archives.

Jessica Taylor portrayed Harriet in 2014, when she was pregnant with her daughter.

The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was then published as a two-volume book in 1852. It was a best seller in the U.S., Britain, and Europe and was translated into over 60 languages.

The book received both high praise and harsh criticism and propelled Stowe and the issue of slavery into the international spotlight.

“Slavery proponents argued that the novel was nothing more than abolitionist propaganda,” the National Archives says. “In the South, and in the North too, people protested that the depiction of slavery had been melodramatically twisted. Southerners particularly promoted the idea that the institution of slavery was benevolent and benign.”

Responding to charges that the book was a distortion, Stowe published another book, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which documented the actual cases upon which her book was based to refute critics’ claims that her work was fabricated and based on supposition.

The novel is a fictionalized account of the pain slavery caused its victims, the struggles slaves endured to escape and travel on the Underground Railroad, and the triumph of escaping to freedom in the northern states or Canada.

Within the first year of publication, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” sold 300,000 copies, and it’s been translated into 75 languages.

Tammy Rundle interviewing historian Michelle Watts at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati.

It was written at a time when women did not have a right to vote, have legal rights, or the right to speak in public meetings. Uncle Tom’s Cabin became an important part of the social fabric and it is thought to have added to the fire that started the Civil War and led to the emancipation of southern slaves by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

Harriet got information from so many sources and perspectives and channeled them through a fictional story which mirrors what’s really going on, Hartlieb said.

“She was the social media of her time, the ability to change public opinion,” she said, noting the novel got pushed aside in subsequent decades and was not thought of as great American literature.

For most of the 20th century, it got a bad rap, and most people didn’t read the book. The way we think of the term “Uncle Tom” today is not what Harriet meant, she said.

Uncle Tom in the story is “a Christ-like martyr figure,” Hartlieb said. She equates slavery with sin and Harriet sees him sacrificing of himself. He lets himself be sold, purposely does not run away, so his wife and children don’t get sold.

By the end of the novel, Tom also sacrifices himself, since he knows where freedom seekers went, but doesn’t give them up. Some people think he didn’t press for his freedom and so was a race traitor, a sellout to the white man, Hartlieb said.

Back then, even though it was a hugely popular book, more people saw the plays based on it, she said. “They evolved into this blackface minstrel show and the character of Uncle Tom becomes this buffoonish, blackface minstrel character, which just compounds the idea of the sellout. The term Uncle Tom really is quite different than what Harriet intended and since nobody in the United States has read the book today, it’s hard to make people see that.”

Theater companies that adapted the book for the stage traveled the country, using their own versions, without anti-slavery messages, and adding spectacle to draw crowds, according to the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

Historian Chris DeSimeo being interviewed for the documentary.

“Because her strict Congregationalist upbringing forbade going to the theater, Stowe was not comfortable collaborating on stage productions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” the site says. “Unfortunately, 1852 copyright laws did not protect fictional works from being adapted into plays without the author’s permission.”

Harriet famously met President Lincoln at the White House on Nov. 25, 1862, during the Civil War.

“She’s very famous at this point,” Hartlieb said, noting she visited a son in D.C. who was a Union Army solider. She pressed Lincoln for passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, which was adopted about a month later, Jan. 1, 1863.

The apocryphal quote attributed to Lincoln upon greeting Harriet – “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!” – may not be true, but the sentiment was, Hartlieb said. “This is the turning point for many Northerners – reading ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ makes them go, ‘Yeah, slavery is bad.’”

The novel dramatization really grabbed the public attention, by basing them on real people, which the author explained in her 1853 book, “A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

“It’s like a gigantic bibliography,” Hartlieb said. “It really does demonstrate all the research she had done.”

“Harriet is taking these episodes and making them into a coherent story for people,” she said. “They get on the side of and rooting for these characters. She’s able to humanize it, even to the fact of showing the character of Eliza Harris – we see her trajectory using the Underground

Tammy Rundle, left, with Christina Hartlieb at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House.

Railroad. The way she’s described in the book makes white women in the North relate to her because she’s not a dark African-American. She’s very light-skinned. ‘This could have been me,’ you know? ‘What would I do if they said they were gonna take my baby away’?”

“It humanizes the emotions and also makes it more relatable to people,” Hartlieb said.

Langston Hughes called “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” the “most cussed and discussed book of its time.” It sold even more copies abroad than it did in the United States — 1.5 million in one year in Great Britain.

When Stowe visited England in 1853, invited by anti-slavery groups, she was rushed by excited crowds. During her five-month stay, she traveled the country – attending many anti-slavery rallies and was presented with the Stafford House Address, a 26-volume leather bound petition signed by more than 563,000 British women asking their American sisters to work to abolish slavery. Britain outlawed slavery in 1834.

In 2018, BBC Culture surveyed writers around the globe, and they picked “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” as #2 among books that most shaped the world.

Homer’s “Odyssey “ topped the list — examples of the different ways in which respondents interpreted a “world-shaping story.” with the ancient epic having survived generations of retelling, while Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel was commended for being “the first widely-read political novel in the U.S.”

Christina Hartlieb is executive director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati.

Stowe used her fame to petition to end slavery – touring nationally and internationally, speaking about her book and donating some of what she earned to help the anti-slavery cause, according to womenshistory.org. She also wrote extensively on behalf of abolition, most notably her “Appeal to Women of the Free States of America, on the Present Crisis on Our Country.”

During the Civil War, Stowe became one of the most visible professional writers. The 1862 Lincoln quote — published in a 1911 biography of Stowe by her son Charles — has been called into question, as Stowe herself and two others present at the meeting make no reference to it in their accounts (and Charles was only a boy at the time of the meeting).

From Maine, the Stowes moved to Andover, Mass., where Calvin was a professor of theology at Andover Theological Seminary (1853-1864).

In 1873, Stowe and her family moved to Hartford, Conn. (becoming a 17-year neighbor of Mark Twain when he built his sprawling home in 1874), where she remained until her death in 1896, summering in Florida. She helped breathe new life into the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, and was involved with efforts to launch the Hartford Art School, later part of the University of Hartford.

Literally becoming Harriet

Jessica Taylor (like her husband Tom, a Q-C theater veteran) hasn’t seen “Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe” yet, and can’t wait. She poured her heart and time into preparing for the role.

“I devoured as many books as I could about Harriet,” she said this week. “I read ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ first and I read all kinds of biographies. And I read some of Weld’s works as well.”

“This was a period in Harriet’s life that wasn’t written about much,” Taylor said. At the Lane Seminary debates, the young writer mainly listened.

Jessica Taylor portrayed Harriet in 2014, when she was pregnant with her daughter.

“They’re not certain what she said or how much she said,” Taylor noted. “She was a very quiet person, so for her to stand up at all would seem a little strange. Even when she was a famous author, she didn’t speak. She let her husband speak for her.”

“Harriet was very quiet, introverted. She lived through her writing,” she said. “It was really the loss of her son that sparked this writing. She empathized with these slaves who had been losing their children.”

Taylor wanted to portray Harriet as a deep, sensitive thinker, internalizing the debates.

“She didn’t expect anything great out of her life,” she said. “She didn’t have larger ambitions than being this small writer. She didn’t think she’d change the world the way she did. She was finding her own place, doing her own thing, and that’s what ended up changing it.”

Harriet was in the shadow of her older sister, Catherine (a teacher), and her personality really came out as a writer, both as members of the Semi-Colon Club, Taylor said. “She wrote these really witty, satirical pieces, and that’s the way she really showed who she was, through her writing.”

Jessica was pregnant during the 2014 filming of “Thunder” and related to Harriet as a mother. She and Tom Taylor (who played Theodore Weld) welcomed their daughter, Avery, May 30, 2014.

“I told Kelly and Tammy, I don’t think I’d have the same performance that I did had I not been pregnant at the time,” she said. “I can understand that Harriet was inspired to write this, and the need to find some healing in writing it as well. I was actually pregnant during the whole film, except the last scene – I was one month postpartum, so that whole experience enshrouded in becoming a new mom, which was

“Thunder” stars Tom Taylor, left, Jessica Taylor and Janos Horvath at the sold-out Cincinnati premiere in March 2019.

definitely a big changing factor for me in relating to Harriet.”

Taylor admired how Harriet was able to write while raising six children.

“If I were her, I feel like I’d have to be out of the house to write, with all the noise and distractions,” she said.

Tom and Jessica went to the Cincinnati premiere of “Thunder” in March 2019, with Janos Horvath (and his wife Jennifer), who played Lyman Beecher. They did a Q & A after the film showing.

“It was nerve-wracking because a lot of historians were there, and people who were related to some people we’re portraying,” Taylor said. “They had wonderful things to say and were so supportive. I was tearing up because these are the people that know. One woman said, ‘I won’t think of Harriet again without thinking of you’, which was immense.”

The Cincinnati premiere of “Sons & Daughters of Thunder” was March 23, 2019 at the Garfield Theatre. The Q-C premiere was the week prior, March 16, 2019, at the Putnam Giant Screen Theater, Davenport.

In Cincinnati, the Taylors visited The Rankin House, and at dinner on the Kentucky side of the river, they met George Clooney’s parents. “We went everywhere,” Taylor said. “I was seven months pregnant, so it was exhausting, but it was pretty cool. We had to let out my dress a little bit and we had a fundraiser at the house, where we said some of our lines.”

“Sons & Daughters of Thunder” won seven awards in August 2020 from the Iowa Motion Picture Association.

“It was a great turnout at the Harriet house that night. There are so many people who love her and support her,” she said. “They liked to quiz me, and said you need to know everything.”

“It’s definitely a huge, huge part of Cincinnati’s identity, this story,” Taylor said.

It’s not as known nationally, since the years afterward – with the Civil War and freeing of slaves – overshadowed them, she said. “It’s the part that’s happening prior that gets overlooked, and there’s this big explosion later, that actually gets all the attention.”

At the Rankin House, they could see across the river, and see how far the slave journey took, Taylor said. “The thing that really sat with me for a long time was, they didn’t know who was going to answer the door, whether it’s friend or foe. They just made this huge trip and don’t know if they’re gonna be sent back. It was this emotional reaction.”

The other part she was deeply affected by was the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, with a small slave house.

“There were etchings on the wall and you could touch it,” Taylor said. “Like you were connected with that person. At the Freedom Center, they have a room with stones of all the slaves that passed away on the slave ships coming over. To sit there and really take it in was a lot. You see these individual stones – it was just incredible.”

Jess and Tom have done a ton of Q-C theater together, and bonded over doing the “Thunder” project.

“Once he was cast as Weld, we had back and forth dialogue,” she said. “We were at our high-top table with books and highlighters and notes. We’d stay up late talking. It was also really great to have this project to work on together; I found out I was pregnant the same day Tom got cast in the movie. I was going to be really envious if you get to do this and I don’t.”

“It was great to have that focus on as we were becoming new parents – to have that project that we were working on together and becoming even closer,” Taylor said. “Avery still doesn’t care to watch us on screen. But she always says, ‘That’s mom and dad,’ and “I’m in mom’s belly.’

“One of the first takes of the first day, I almost missed my first line because when they called ‘Action,’ Avery kicked,” she said. “It was those moments I’ll always remember.”

“I feel like it will be blast from the past to see it,” Taylor said of the new doc. “I’ll the research and memories will come back again.”

Her full-time job (since last month) is director of communications for St. Paul Lutheran Church, Davenport, where she gets to write a lot.

Dee Canfield recording as Harriet in the Rundles’ home.

“I’ve always been a writer and love to write, and I find if I try to write in a certain style, I find an author I want to emulate,” Taylor said. “I pulled out ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ the other day, giving it a look. I can get some ideas from Harriet and her writing.”

Dee Canfield (also a theater veteran) went to Rock Island High School, and recently recalled reading “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” the summer she was 16.

“That was just one of the most profound experiences of my life, reading that,” she said. “That’s when my social conscience was born. The next summer I read ‘Les Miserables.’ It was just a profoundly troubling and painful thing to read, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Canfield has been thinking a lot about the Black Lives Matter movement and racial equity in the Q-C, remembering when she was in school, they didn’t cover much at all about slavery.

“There was nothing in my formal educational background that put any kind of understanding in what it meant on the human level,” she said. The reason Stowe’s book (among 30 she wrote) was so powerful was “that really opened my eyes to what slavery meant to real people,” Canfield said.

“People say, with the violence and racism today, when we see the ugly manifestations, they say that’s not who we are,” she said. “But it is who we are — we have a history, 400 years of history. It’s just our history; people are beginning to wake up, see a fuller picture of what life is like for people.”

Canfield had never done a film voice-over before recording at the Rundles’ home; she’s also heard as Harriet at the start of “Thunder.”

“I appreciated the significance of what I was doing. I really valued the opportunity to portray her voice,” she said. “That was really meaningful to me to be able to do that…My first reading would have been fine if it were on stage, but the Rundles said you need to bring it way down, be much more intimate.

“Just as television and movies are a step down from the bigness and broadness of what you do on stage, film narration is more subtle,”

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Joan Hedrick, left, with Tammy Rundle.

Canfield said. “Your voice is the medium for the ideas to come through.

“Doing these films was an education for me. I didn’t know anything about her or her father,” she said. “The debates at Lane Seminary, that was the beginning of the end of slavery. They’re such important stories.”

Canfield loves the new doc, learning from experts on Harriet, and how her Ohio experienced shaped her.

“One of the things I liked about ‘Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe,’ during the reminiscences I narrated, they were done from the point of view of traveling through water, sort of like meandering of the mind, following the river,” she said. Of the Rundles, “I love their gentle approach to things. They take things that are of significance that much has been overlooked,” she said.

“The Rundles were amazing to work with,” Canfield said. “When they invited me to do that, I was petrified. I had done tons of theater work, but never done any film narration. It’s a very different talent.”

A long, patient journey into film

The Rundles showed a preliminary cut for an Ohio Humanities event in September 2019 at Xavier University in Cincinnati, attended by Hartlieb and DeSimio.

Moline filmmakers Tammy and Kelly Rundle.

“It was a very lively event and a good discussion,” Kelly Rundle said.

“Part of the benefit of doing preview screenings of a film, before we air it or premiere it, is we can see how the audience is reacting, and see if things are clear – if there’s anything we need to improve,” Tammy said.

They didn’t plan on doing a separate Harriet film after the long period of research, writing and filming “Thunder,” but did because she was so interesting as a subject.

“Her major work was really a product of living in the Midwest,” Kelly said. “It wasn’t the Midwest then, but it is now. She’s sort of now regarded as a product of the Midwest. But Tammy’s really the one who pushed for that.”

“I felt like we had a really good jump-start on the research on Harriet because of ‘Sons & Daughters of Thunder.’,” Tammy said. “What was interesting to us was how much Cincinnati transformed her, or helped to build her confidence I think, as a writer. Her experiences there really changed her and influenced her, in terms of writing that epic book that she wrote.”

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House is actually the Lyman Beecher house, where the family moved to in 1832 (she had 10 siblings). Harriet and Calvin married there, and they lived in the house from time to time.

It’s the last remaining structure from the Lane Seminary campus, the president’s house.

“When you first visit there, you see this house surrounded by this urban setting,” Kelly said. “It’s a beautiful little secret, in a way. It’s got trees around it; it’s this little oasis, a haven, in the middle of what’s really a very urban area.”

Kelly Rundle filming in the John Rankin House, one of the key stops on the Underground Railroad for runaway slaves.

The Rundles filmed “Thunder” mainly in 2014, with one of the first shoots at the Beecher house, and the Harriet doc was filmed in 2018. They filmed in Hartford for both as well.

The Victorian house in Hartford is known as the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. Its website says the author’s “courage as she picked up her pen inspires us to believe in our own ability to make positive change. Uncle Tom’s Cabin challenges us to confront America’s complicated past and connect it with today’s issues.”

“It’s true with many of the stories we’ve worked with – they are history stories, but they feel oddly contemporary sometimes,” Kelly said. “I suppose it’s a consistent thread of human nature, human conflict, and I think you see gradual progress. We see progress happening very slowly.

“We wish that the stories didn’t seem familiar,” he said. “That we weren’t still struggling with issues connected to Native genocide and the slave trade, but we still are.”

Hartlieb, executive director of the Cincinnati house, helped organize the 2019 Cincinnati premiere for “Thunder” (selling out two shows in a 150-seat theater) and recommended interview subjects for “Becoming.”

Of “Thunder,” it was illuminating to actually see the characters portrayed, rather than just reading about them, she said Thursday.

“Seeing the emotions of people, arguing very articulately about the idea, which was very radical at the time, brought it to life,” Hartlieb said.

She likes the “Becoming Harriet” doc because it brings together all the things that were happening in Cincinnati. “It shows how what was

Harriet’s home in Hartford, Conn., where she lived next to Mark Twain.

happening really shaped what Harriet was doing.”

Learning Harriet’s story forces us to focus on persistent racial inequities that continue to this day in the U.S., she said. “What is the root of that and how do we combat it today? We stress in our tours and programming, that is something that’s happening and we want to make people aware of why it happened in the past and how do we move forward?”

In August 2020, at the Iowa Motion Picture Association awards, “Sons & Daughters of Thunder” film won seven awards, out of eight IMPA nominations. It won five top Awards of Excellence:

- Best Live Action Entertainment — Long Form (60 minutes or more)

- William Campbell for Best Original Music Score

- Thomas Alan Taylor for Best Actor

- Kimberly Kurtenbach for Best Supporting Actress

- Kelly Rundle for Best Direction — Long Form

Filming for “Thunder” took place at the Dillon Home Museum in Sterling, Ill., the Jenny Lind Chapel in Andover, the Karpeles Manuscript Museum and Augustana’s House on the Hill in Rock Island, Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati, and Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford.

The Rundles later were nominated for four Mid-America Emmys, in November – three for “Thunder” and one for the Harriet documentary, but were shut out from winning.

Registration is required for the Feb. 18 library event, at http://events.bettendorflibrary.com/event/4780047

Becoming Harriet Beecher Stowe is slated for release on DVD by the end of this month. For more about the film, visit www.HarrietBeecherStoweMovie.com, and you can pre-order the DVD HERE.