From Polio To Covid, Global Vaccine Mobilization Has A Long History

By Craig Cooper

The coronavirus sweeping across the globe may seem to be unlike anything most have experienced.

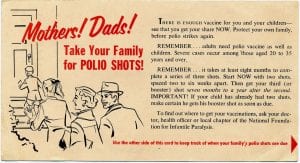

People lined up in droves nationwide for the polio vaccine.

But if you are 60 years old or older, mass COVID-19 vaccination efforts may seem vaguely familiar. You may remember another frightening and uncontrolled viral outbreak.

We have been down this path before.

There was danger in the water for parents and their children 60 years ago. The warm months of summer were polio season. Exposure to waters polluted by human fecal matter and ingested by others could be life altering and possibly deadly.

Polio outbreaks were striking American children, resulting in quarantines in cities and small towns.

Polio did not discriminate by location, gender or age.

Comparable in ways to the COVID-19 pandemic battle, paralytic poliomyelitis, referred to as infantile paralysis, or just polio, was devastating and terrifying. Although most people with polio recovered quickly and without serious prolonged problems, others suffered paralysis or death from the disease’s attack on the nervous system.

There was no effective prevention at the time for polio. Treatments were largely ineffective. Polio was fatal to as many as 5 percent of children with the progressive form of the illness. In adults, 15 to 30 percent of adults affected with advanced illness died.

Because transmission was by respiratory path and fecal material to oral ingestion, swimming pools and beaches shut down in the most dangerous summer months. Movie theaters closed. If the theaters were open, patrons were advised to keep distance between themselves and others. Now we have given the practice a name … social distancing.

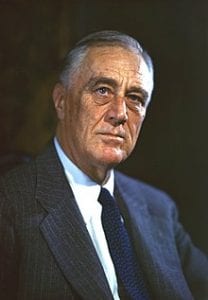

FDR Stricken

By the early 1950s, there were 25,000 to 50,000 new cases of polio each year in the United States.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

The most prominent American stricken was future President Franklin Roosevelt, who was stricken as a young man in 1921.

Children and adults with polio were isolated from their families for days or months in hastily opened isolation hospitals. When the virus affected the ability of polio patients to breathe, many were placed in an iron lung to assist in respiration.

Another treatment was physical therapy. Children who lost the ability to walk relearned walking with therapy.

Polio was so contagious and potentially serious that a child or teenager could be whisked away. That happened to a Davenport High School football player named Jack Wolfe, according to a Quad-City Times story from the 50s. The 16-year-old complained of “stiffness’’ in his back and legs after a game. The next morning he was removed to the Scott County polio isolation hospital. He was diagnosed with polio the following day.

My aunt, Marlys Keith of Reinbeck, Iowa, was at home with my cousin Sandy, a toddler, when both had back pain. They were driven to Iowa

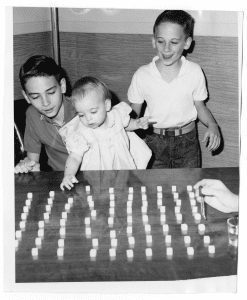

Children in the 1950s look at the various polio vaccines as they’re prepared

City by my uncle Jim and the town’s doctor to be admitted to an isolation hospital.

“It was a one-floor building that only had polio patients,’’ Aunt Marlys recalled recently. “It was a bad experience. I remember that. Sandy was only there overnight and was released but had to learn to walk again.

“We were in isolation. No one could see us, kind of like today with COVID-19. I remember being told by another patient to keep all the pills the staff gave us and take them just before physical therapy in the afternoon so we’d be able to do the exercises and maybe have a better chance to get out. We did that.

“There was a person in an iron lung in the hallway right by my room. That patient died. I think I was there 10 days. I could still walk but I don’t think I walked very well right away. I lost a lot of strength.

“The next year in our little town, several more people got it.’’

Similar to COVID-19 restrictions, visitation to isolated polio patients was restricted. Parents would wait on the street outside. There are photos of people climbing ladders propped up outside isolation hospitals to make themselves visible to their stricken child.

Also similar to our COVID-19 experience, the country needed assurance someone was doing something. Scientists were looking for solutions 60 years ago, too, when the breakthrough was announced.

Vaccine Breakthroughs

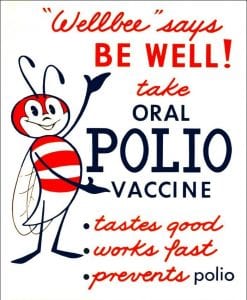

A number of PSAs were put out to introduce and popularize vaccines.

In 1955, Dr. Jonas Salk’s first polio vaccine was approved. The newspaper headlines about Salk’s vaccine breakthrough were two inches deep at the top of the front page. This was a global development and the reaction was global.

Salk’s initial vaccine was inactive poliovirus delivered by injection. Following a clinical trial that Scott County patients were part of, school students across the country got the Salk vaccine first in 1954.

Salk was a national hero. There was celebration of Salk’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.’’

Albert Sabin developed the second polio vaccine, a live, weakened virus version. Sabin’s version could be taken orally, making it easier to administer.

Wellbee, a mascot for the polio vaccine, is a familiar sight to kids who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s.

Sabin’s vaccine could be administered as a liquid, or dropped onto ordinary sugar cubes and consumed. Millions of Americans got those sugar cubes.

Getting the polio vaccine to the public required a national mobilization.

It was a long time ago, but there is still a memory of doses of the sugary tasting drink in a small cup and the sugar cube delivery system.

In schools, fire stations, churches on Sundays after services, entire families, entire neighborhoods, would line up for the vaccine. There was little controversy about the vaccine because the alternative could be so devastating.

The global experience with polio has come up lately as scientists all over the world develop vaccines to stop COVID-19. Several versions of vaccines are now available.

The lesson from polio vaccines is that they were effective and safe. The disease has been eradicated in much of the world.

As more Americans gradually gain access to COVID-19 vaccines beginning this week, we can be hopeful the new COVID-19 vaccines will be as safe, effective and accepted as the polio vaccine has been.

The global mobilization to control the virus will require patience and faith in science but we have been asked for both as a country before and came through for each other and for future generations.