Dark Quad-Cities Tales to be Told Sunday in Free GAHC Program

Have you heard about the Quad-Cities’ own serial killer? The tale of an angry brothel owner in Bucktown? What about Davenport’s connection to the Barrow gang (of “Bonnie and Clyde” fame)?

You can learn about these urban legends and historic Davenport’s dark past in a virtual program presented Sunday by Kelly Lao, executive

Kelly Lao is executive director of the German American Heritage Center.

director of the German American Heritage Center & Museum. The free 2 p.m. Zoom lecture includes Davenport artist Bruce Walters’s famous Halloween inspired photography and ominous art works.

Milan serial killer Henry Bastian was a German immigrant farmer, near Camden Park. He would hire farm hands who were other German immigrants to work for a season. Once the season was over and it came time to pay the hands and send them on their way, they were never heard from again, Lao said Thursday.

According to a Davenport Public Library blog, when 21-year-old Frederick Kuschmann was found dead on the evening of Feb. 29, 1896, in Black Hawk Township near Milan, it appeared to have been a tragic accident. His body was found along a roadside by his employer, Henry Bastian.

February 29th had been the last day of his employment. When asked by the authorities, Bastian stated that on that day he had paid the young man $79 in wages owed and watched him ride off to visit his family in South Rock Island.

Kuschmann was to return the next day with a wagon to collect his belongings at Bastian’s suggestion. Bastian also stated that the horse on which Frederick left seemed irritable and hard to control.

Henry Bastian of Milan was suspected of killing up to nine of his farmhands.

Upon finding the body, Bastian immediately sought assistance. Dr. Eddy of Milan, was called upon and later reported there was nothing he could do for Frederick. A coroner’s inquest held March 2 returned a verdict of accidental death. Poor Frederick Kuschmann was likely thrown from his horse. Not everyone agreed with the verdict.

On March 3, the family of Kuschmann made it known they did not feel this was an accident. Bastian had said Kuschmann rode off with $79, but only a few silver coins were found at the scene. Also, Frederick’s head was severely bruised and cut with no other signs of trauma to the body. That did not seem to fit with being thrown from a horse.

Authorities began to look into the case again. It probably did not hurt the Kuschmann family that Frederick’s uncle was a former alderman in the city of Rock Island and knew many local officials.

It soon became apparent that the death of Frederick Kuschmann was not an accident. But who would do something so horrific?

It brought to mind a recent event that had left people puzzled. Two nights before Kuschmann’s death, farmer William McLaughlin’s barn had been set on fire. The elderly Mr. McLaughlin remained in the farmhouse while others went to extinguish the flames.

In the midst of the commotion, an unknown man entered McLaughlin’s house and began to go through the family’s parlor. McLaughlin surprised him and he ran off. The family was rumored to have kept a large amount of money in the house; the man was probably after it. Because the Bastian farm adjoined the McLaughlins’ to the southwest, many people believed the same man committed both crimes and was

Davenport artist Bruce Walters created these ominous photographic images.

now on the loose.

On March 7, the Rock Island County Board of Supervisors issued a reward of $500 for the capture of Kuschmann’s murderer. Rumors ran rampant as the police worked to solve the case.

The murder and fire even caught the attention of the much larger Chicago Tribune newspaper. Citizens on both sides of the Mississippi River were on edge, wondering where this fiend would strike next.

By March 13, rumors were circulating that Kuschmann had not been murdered on the roadside. Evidence suggested he had been attacked elsewhere, his coat wrapped around his head, and he was then driven to the spot where his body was placed. His bloody but undamaged coat was found a short distance away.

Henry Bastian was a 26-year-old married farmer with one young child and another on the way. He had taken over the family farm from his parents, Christian and Catharina, a few years before. His older sister was also staying with the family at the time, as his wife Eva was expected to soon give birth.

The police questioned the Bastian family about Kuschmann’s last day at the farm. Eva Bastian had been sent by her husband to visit her parents that afternoon, and was not at home when Kuschmann was paid and left for the night. Henry’s sister Carrie claimed to have been in the bath and also did not see Kuschmann leave. As for Bastian, he never wavered from his original account.

The police soon learned that Henry was in financial trouble. They also began to suspect that he had forged his father and wife’s names to

Davenport artist Bruce Walters created these ominous photographic images.

mortgage the farm.

Bastian, it appeared, had an ingenious plan. He hired men to work his farm for a set period of time. Stating he did not have the money to pay them weekly, he would then offer them room and board and a promise to pay a lump sum at the end of the contract. On or near the last day of the man’s employment, Henry Bastian would kill him and bury the body on his farm.

Early on the morning of March 13, 1896, Bastian’s was found in the granary of the farm. He had committed suicide.

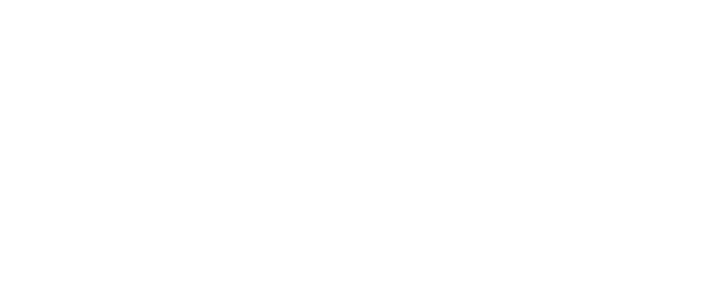

Joe Palmer was an associate of the Barrow Gang.

He was buried on March 15th (his 27th birthday) in Chippiannock Cemetery, Rock Island. Only a few days later, his wife would give birth to a little girl.

A Barrow gang member by the river

On June 14, 1934, Davenport Police Officer Elmer Schlueter was patrolling the levee area near LeClaire Park when something out of the ordinary caught his eye.

It was a well-dressed man in a gray checkered suit carrying a large briefcase, according to the Davenport library. He drew a gun and managed to disarm the officer. He forced Schlueter down the path leading to the baseball stadium.

At that moment former alderman and current secretary-treasurer of the Davenport Baseball Club, Al Schultze, was driving towards the men from the stadium. The armed man stopped Schultze’s car, forced Schlueter and himself into the back seat and ordered Schultze to drive. They headed along Rockingham Road west towards Buffalo.

Officer Elmer Schlueter and Al Schultze would soon learn they had been kidnapped by Joe Palmer, murderer and part-time member of the Barrow Gang.

The gang had made headlines starting in 1932 for not only bank robberies, but murder as well. Barrow members Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker had been shot and killed on May 23, 1934 in Louisiana. The remaining free gang members were doing their best to avoid arrest. They were wanted in several states for their numerous crimes.

Witnesses immediately alerted the Davenport Police Department to the kidnapping. The police department was faced with two scenarios. The first being this was “just” a kidnapping that had taken place. The second scenario was the possibility this was part of a larger heist. With all officers on alert searching for the kidnap victims would other criminals be waiting to stage bank robberies in an unprotected city?

Witnesses immediately alerted the Davenport Police Department to the kidnapping. The police department was faced with two scenarios. The first being this was “just” a kidnapping that had taken place. The second scenario was the possibility this was part of a larger heist. With all officers on alert searching for the kidnap victims would other criminals be waiting to stage bank robberies in an unprotected city?

The police department split its resources sending some officers to cover local city banks while all others went out in force to find the missing men. The Scott County Sheriff called on their vigilantes to go to county banks to cover them in case of attempted robberies.

Soon Schultze’s car was located on the side of the road near Blue Grass. It was then reported that Walcott veterinarian, Dr. W. H. Fitch, had never returned from a call he made to the Bernick farm in Blue Grass.

By 2:00 p.m. a report was made of a car matching Dr. Fitch’s driving rapidly west on Route 6 near Walcott. Officers immediately started in pursuit and cities along the way were notified to be on the lookout.

The Colonel Davenport House on Arsenal Island, long before its restoration. Lao will discuss George Davenport’s murder in his own home July 4, 1845.

Davenport Police Chief Sam Kelly ordered all officers not on duty to head to Blue Grass and Walcott. They searched all wooded areas along the roadside to see if they could find the victims. All they found were veterinarian supplies and a briefcase. Even a local airplane was put into service to fly over the county to try to spot either the car or the men. No trace could be found.

Finally, at 3:45 a.m. on June 15 a call came into the Davenport Police Department. It was Officer Schlueter. He, Al Schultze, and Dr. Fitch had been released by their kidnapper in St. Joseph, Mo.

A meaty, drunk story about Bucktown

While not nearly as scary, Kelly Lao will also discuss the bawdy area of downtown Davenport known as Bucktown. It also was called the “Tenderloin district,” as the police who worked the beat there were paid to look away, and thus able to afford a prime piece of meat, she said.

During the heyday of Bucktown in 1909, this is a view of the Government Bridge over the Mississippi River.

In the late 19th century, Davenport jocularly called itself “the free and independent state of Scott,” as the county defied the liquor laws of the state of Iowa (such as prohibition). The bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Davenport called the city “the wickedest city in America,” because of Bucktown.

The New York Herald Tribune said: “The title of worst town in America has now been snatched from the brow of New York City. New York is a quiet milk station compared to Davenport, Iowa.” This reputation was garnered from Bucktown, with its many brothels and decadent night life, Lao said.

After the speakeasys would close down for the night, the working girls could hear money going “clink, clink, clink,” into a cigar box – “they said it was the ghost of an old Madame counting the evening’s take,” she said.

Sunday’s event is free, but donations are appreciated. Participants who reserve a ticket will receive an email with the Zoom link. Reserve your

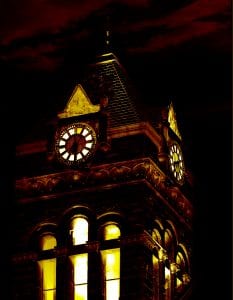

An image of Davenport City Hall’s clock tower by Bruce Walters.

ticket by calling 563-322-8844 or visit Eventbrite.com.

November talk explores Q-C link to World War II

As part of GAHC’s current exhibit – “Valor and Victory Gardens: WWII in the Hawkeye State,” a collaboration with Dr. Art Pitz and the Jewish Federation of the Quad Cities — Art Pitz will speak on the experiences of people in the Quad-Cities during World War II, on Sunday, Nov. 8 at 2 p.m. It’s also a free Zoom lecture.

He will enlighten the public with stories of the dedication and hardships faced by those on the homefront, as we went from the Tri-Cities to the Quad-Cities during wartime, Lao said.

Not only did local people answer the call to serve following the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, but even more Quad Citizens served from home. People who could not serve had their own role to play during

The GAHC’s World War II exhibit will be on display through January 27.

WWII, from scrapping and canning to work being done on the Rock Island Arsenal.

In the GAHC exhibit (through Jan. 27, 2021), you can learn war stories and see objects from local heroes and survivors. Learn how our region participated in the war, see artifacts from those on the Western and Pacific fronts, view images of Germany prior to and after bombing campaigns, and hear the stories of survivors of the Holocaust from our community in this exhibit.

You can pre-register for the Nov. 8 talk and receive the Zoom link by signing up at

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/the-qc-during-wwii-tickets-124927117371. A link will be sent on the Saturday prior to those who register.

The GAHC – at 2nd and Gaines streets, Davenport — is open on Tuesdays-Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., and on Sundays from noon-4; closed on Mondays. For more information, visit www.gahc.org.