Worshipping at the Church of Stephen Sondheim, Mourning the Legendary Master’s Death

Saturday in the Arts is a weekly feature covering a trend, subject, event or personality of local interest. It runs every Saturday morning on your site for the best entertainment and arts coverage in the area, QuadCities.com!

God is dead.

Well, maybe not THAT God, but did anyone ever see Stephen Sondheim and God in the same room? And now, He is gone – the legendary Broadway composer and lyricist died Nov. 26, 2021 (fittingly on Black Friday) at age 91 – but will never be forgotten, since we have the sacred texts.

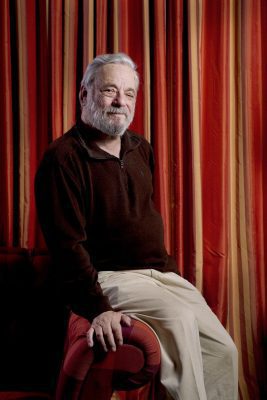

In recent years, especially since the 2016 death of my mother, I have had grave doubts about my religious faith, but my faith in Sondheim (who many worshipped as a god) never, ever wavered. As a professional musician and Broadway fanatic myself, I have genuflected at the altar of the man for decades – and like God (bearded and wise), he has often seemed incomprehensibly superior, above mere mortals, the font of creation, forbidding and remote.

But always worthy of praise and an endless source of inspiration, fascination and debate. Whether you love or hate Sondheim (or don’t know the first thing about him), there’s no possible denying that the guy was a freaking genius and all too human.

The lights of Broadway’s marquees will dim for one minute on Wednesday, Dec. 8, at 6:30 p.m. Eastern in memory of the immortal Sondheim, who died suddenly at his home in Roxbury, Conn., and was still at work at a new musical, titled “Square One.” (Can anyone complete it, please, a la the Mozart Requiem?)

Sondheim was active up until the end — appearing on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert in September, and attending the Broadway revival of his “Company” in November.

“It is impossible to measure Stephen Sondheim’s impact on the world of musical theatre,” said Charlotte St. Martin, President of The Broadway League. “During a career that spanned nearly 65 years, he created music and lyrics that have become synonymous with Broadway — from Gypsy and West Side Story to A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Follies, Into the Woods, Sweeney Todd, Sunday in the Park with George, and too many more to name. It is hard to imagine Broadway without him, but we know his legacy will live on for many years to come, including in this season’s revival of Company opening December 9.”

Filmmaker Steven Spielberg – whose electrifying, stunningly relevant new version of the classic “West Side Story” is due to finally hit theaters Dec. 10 – said:

“Stephen Sondheim was a gigantic figure in American culture — one of our country’s greatest songwriters, a lyricist and composer of real genius, and a creator of some of the most glorious musical dramas ever written. Steve and I became friends only recently, but we became good friends, and I was surprised to discover he knew more about movies than almost anyone I’d ever met. When we spoke, I couldn’t wait to listen, awestruck by the originality of his perceptions of art, politics and people — all delivered brilliantly by his mischievous wit and dazzling words. I will miss him very much, but he left a body of work that has taught us, and will keep teaching us, how hard and how absolutely necessary it is to love.”

Director Steven Spielberg (center) with the leads of the new “West Side Story.”

The composer over the years has routinely been called a god, including the headline of a 1994 New York magazine piece: “Is Stephen Sondheim God?”

That reputation influenced the creation of the first new Sondheim song in a while, in 2010, for the revue “Sondheim on Sondheim,” appropriately titled “God.”

True to his genuinely humble, self-critical nature, he penned a snarky, self-deprecating number for the show, which starred Barbara Cook, Vanessa Williams, Tom Wopat and, thanks to several prerecorded videos, Sondheim himself.

Here are excerpted lyrics:

Still you have to have something to believe in

Something to appropriate

Emulate

Overrate

Might as well be Stephen

Or to use his nickname:

God!

We’ve got God!

Look who’s God!

Certainly, in the rough past two years, everyone has needed something to believe in – something immutable, unchanging, dependable, like Sondheim himself.

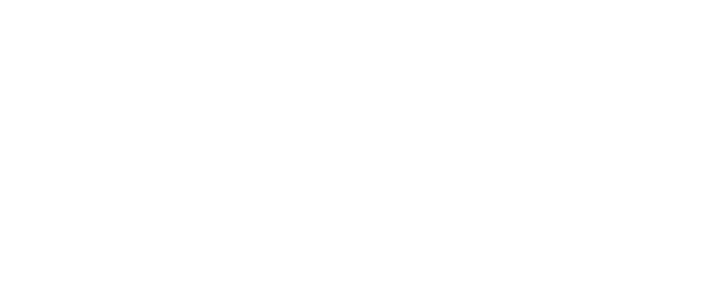

In one of many, many touching tributes I’ve seen in the past week, few are as moving as from one of his most famous acolytes – Lin-Manuel Miranda, another multi-hyphenate genius.

Lin-Manuel Miranda reading from Sondheim’s “Look, I Made a Hat” at a packed Times Square on Sunday, Nov. 28.

Two days after Sondheim’s death, on Sunday (Nov. 28) – of course – Miranda read from Sondheim’s commentary about the reverent choral song, “Sunday” from his Pulitzer-Prize winning “Sunday in the Park With George.”

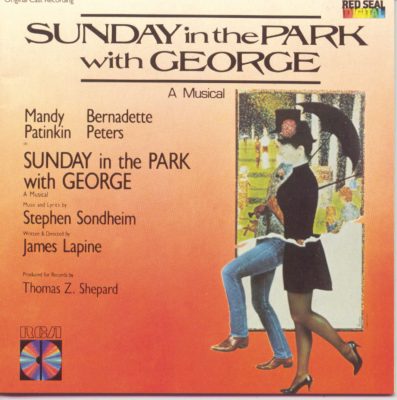

Perhaps my favorite of his shows (it is SO hard to choose one), “Sunday” seems the most closely identified with the real composer, as the first act follows the French artist Georges Seurat (a moody, obsessive, groundbreaking perfectionist – sound familiar?) as he creates his pointillist masterpiece “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” (1886), which hangs at the Art Institute of Chicago.

One account of last Sunday’s Times Square ceremony (packed with Broadway performers, including Josh Groban and Sara Bareilles) noted that Miranda offered a sermon of sorts. Forgoing a speech, he opened Sondheim’s “Look I Made A Hat,” the second annotated anthology of the composer’s lyrics, and read from a few passages before the crowd.

“Once during the writing of each show, I cry at a notion, a word, a chord, a melodic idea, an accompaniment figure,” Miranda read from Sondheim’s words. “In [‘Sunday in the Park with George’], it was the word ‘forever’ in ‘Sunday,’” Miranda continued, beginning to choke up. “I was suddenly moved by the contemplation of what these people would have thought if they’d know they were being immortalized.”

When you watch the gorgeous performance of the divine, hymn-like ode (in the show, where the artist assembles all the characters in place in the painting at the end of the first act), Miranda’s eyes literally well with tears when they sing “forever.”

Bareilles told Variety of the performance, “This felt like church. In his remembrance, we did what theater does best. We sang and raised our voices and came together in community.”

“Everybody who’s here has a touchstone for why Sondheim’s music has brought them to this place,” Groban told Variety after the performance. “And whatever part of the entertainment industry we’re in, everybody is here because we were first influenced by Sondheim’s music. To mourn his passing is a crushing blow.”

“‘Sunday,’ is about capturing moments and holding on to them while we have them, even the ones that might seem ordinary,” Groban said. “It’s a song about gratitude, about making sure to hold each other close.”

Miranda’s “Hamilton” premiered on Broadway in August 2015 and has run over 2,000 performances so far.

The day Sondheim died, Miranda tweeted:

“Future historians: Stephen Sondheim was real. Yes, he wrote Tony & Maria AND Sweeney Todd AND Bobby AND George & Dot AND Fosca AND countless more. Some may theorize Shakespeare’s works were by committee but Steve was real & he was here & he laughed SO loud at shows & we loved him.”

Is God real? Still not sure…

Overcoming many challenges

I connected so closely with Sondheim – not only because he’s a deeply emotional, intelligent, brilliant songwriter – but partly because he’s always reminded me of my father. They were both born New York City Jews, five years apart, both profoundly in love with language, and similar in appearance and facial expressions. My dad (born in the Bronx in 1935) was an English major in college and became a neurologist, converting to Catholicism, and settling in Milwaukee.

Sondheim was born March 22, 1930, into a well-to-do Jewish family in New York City, the son of Etta Janet (“Foxy”; née Fox; 1897–1992) and Herbert Sondheim (1895–1966). His father made dresses designed by his mother. The composer grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and, after his parents divorced, on a farm near Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

As an only child, living in the landmark San Remo on Central Park West, he was described in Meryle Secrest‘s biography (Stephen Sondheim: A Life) as an isolated, emotionally neglected child. When he lived in New York City, Sondheim attended the Ethical Culture Fieldston School. His mother sent him to New York Military Academy in 1940, and from 1942 to 1943, he attended George School, a private Quaker preparatory school (my wife is half Quaker) in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he wrote his first musical, By George.

The New Yorker recently said Sondheim infused the musical with complicated, sometimes curdled emotions that Broadway hadn’t dared sing about before.

From 1946 to 1950, Sondheim attended Williams College in northwest Massachusetts, where I applied partly because he went there. I graduated with a degree in music from Oberlin College in Ohio, in 1986.

Sondheim detested his mother, who was said to be psychologically abusive and to have projected her anger from her failed marriage onto her son. “When my father left her, she substituted me for him. And she used me the way she used him, to come on to and to berate, beat up on, you see. What she did for five years was treat me like dirt, but come on to me at the same time,” he said. She once wrote him a letter saying that the only regret she ever had was giving birth to him. When she died in the spring of 1992, Sondheim did not attend her funeral.

When Sondheim was about 12 years old, formed a close friendship with James Hammerstein, son of lyricist and playwright Oscar Hammerstein II, who lived near Sondheim’s mother in Bucks County. The elder Hammerstein became Sondheim’s surrogate father, influencing him profoundly and developing his love of musical theater.

Sondheim met Hal Prince, who would later direct many of his shows, at the 1949 opening of South Pacific, Hammerstein’s musical with Richard Rodgers. The comic musical he wrote at George School, By George, was a success among his peers and buoyed the young songwriter’s self-esteem. When the 15-year-old Sondheim asked Hammerstein to evaluate it as though he had no knowledge of its author, he said it was the worst thing he had ever seen: “But if you want to know why it’s terrible, I’ll tell you,” Hammerstein famously told him.

Lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II (1895-1960) was a surrogate father for Sondheim.

They spent the rest of the day going over the musical, and Sondheim later said, “In that afternoon I learned more about songwriting and the musical theater than most people learn in a lifetime.”

Hammerstein designed a course of sorts for Sondheim on constructing a musical. He had the young composer write four musicals, each with one of the following conditions:

- Based on a play he admired; Sondheim chose George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly‘s Beggar on Horseback (which became All That Glitters)

- Based on a play he liked but thought flawed; Sondheim chose Maxwell Anderson‘s High Tor

- Based on an existing novel or short story not previously dramatized, which became his unfinished version of Mary Poppins (titled Bad Tuesday, unrelated to the musical film and stage play scored by the Sherman Brothers)

- An original, which became Climb High

None of the “assignment” musicals were produced professionally. Can you imagine a Sondheim “Mary Poppins”?

“Sunday in the Park With George” (as did “Rent” and “Hamilton”) won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1985.

In 1960, Sondheim lost his mentor and father figure when Hammerstein died of stomach cancer on August 23, aged 65. Sondheim later recalled that Hammerstein had given him a portrait of himself. Sondheim asked him to inscribe it, and said later about the request that it was “weird…it’s like asking your father to inscribe something.” Reading the inscription (“For Stevie, My Friend and Teacher”) choked up the composer, who said, “That describes Oscar better than anything I could say.”

He also famously remarked that he became a Broadway composer because that’s what Hammerstein did, and that if he was a geologist, he would have become a geologist. Sondheim called Oscar a man of “limited talent and immense soul,” and Rodgers was the reverse.

Hooked on musicals since high school

Appropriately, the first musical I played for was the Rodgers & Hammerstein classic “Carousel” (1945) in spring 1980, which was very influential to the young Sondheim.

He told Frank Rich in 2000 that attending a New Haven tryout as a teen was “a seminal experience of my life. I was completely overwhelmed.” Sondheim and Hammerstein’s son Jamie, both turning 15, were taken as a double-birthday treat to the pre-Broadway premiere. The first song from the show that Sondheim mentions is not ”If I Loved You” or ”June Is Bustin’ Out All Over,” but the sorrowful ”What’s the Use of Wond’rin’,” in which the heroine rendingly predicts that the ending of her love affair ”will be sad.”

The first character he recalled was not among its leads, but the hoodlum villain, a misfit and outcast named Jigger. “I remember how everyone goes off to the clambake at the end of Act One and Jigger just follows, and he was the only one walking on stage as the curtain came down. I was sobbing,” Sondheim recalled, noting often in interviews over his life, that he cried easily (me too!!!)

The teenage Steve hugged Hammerstein’s wife, Dorothy. “’She had a specific fur stole that she wore to every opening of Oscar’s for good luck, and I cried so heavily I stained it.”

For many reasons, “Carousel” became my favorite R & H show, and it was such a great, fulfilling experience to play in the orchestra pit, at age 16. My very first kiss was at a cast party from the girl who played Carrie, and she wrote that she loved me in the program. That’s stayed with me forever.

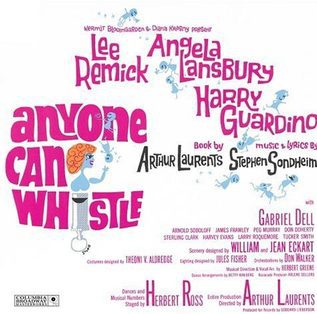

The very next year (40 years ago now!!), the regular high school director (I went to a Catholic high school) was on sabbatical and the two 20-something women who directed my junior-year show made the radical choice to stage Sondheim’s 1964 flop “Anyone Can Whistle.”

Seven years after the 27-year-old wunderkind made his Broadway debut writing the lyrics to Leonard Bernstein’s “West Side Story” music, and just two years after Sondheim’s biggest Broadway hit and solo debut as composer and lyricist (“A Funny Thing Happened on the Way on the Way to the Forum,” the always experimenting pioneer chose a truly bizarre story (penned by WSS and “Gypsy” book writer Arthur Laurents).

“Anyone Can Whistle” (1964) closed after only 9 performances.

The Broadway debut of Angela Lansbury (who 15 years later immortalized Mrs. Lovett in “Sweeney Todd”), “Whistle” is described as an absurdist social satire about insanity and conformity, and “probably the bravest show that Stephen Sondheim wrote, at least until Assassins,” according to Music Theatre International. “A legendary cult show, this wacky, intelligent, highly unconventional musical points ahead to Stephen Sondheim’s groundbreaking work in the 1970s, even as it keeps a foot firmly rooted in musical theater’s golden age.

Anyone Can Whistle tells the story of a corrupt mayoress (Lansbury) who fakes a miracle to revitalize her bankrupt town (through the resulting pilgrim trade) and the ill-fated romance between the rational nurse, out to expose the fraud, and the easygoing doctor who is determined to enjoy the chaos that it brings. In the end, the show delivers a poignant message about the importance of the individual in a conformist society – but not before aiming its still-relevant barbs at government, religion, science and anything else that stands in its way, MTI says.

While it closed after just nine performances, “Whistle” produced a number of enduring songs that are often revived by singers – including the achingly beautiful title song (with a phrase that is a theme for me, “What’s hard is simple, what’s natural comes hard”), as well as “Everybody Says Don’t,” “With So Little to be Sure Of,” and “There Won’t Be Trumpets.”

Sondheim is the undisputed king of wordplay (until Lin-Manuel came along), and one of my favorite lines is at the end of this verse in the French-style “Come Play Wiz Me,” the seductive Fay sings:

If you will play wiz me,

Mon cheri,

Though we may not agree

Today,

In time-

Mais oui! –

We may.

In high school, the Sondheim score was such a mountainous challenge, that I was one of two rehearsal pianists, until the other dropped out, and I played all performances. Much of it was insanely difficult (a trait the man is often cursed for), but so satisfying. A cherished memory that year was at the show reunion dinner, I was given a standing ovation. At his death, actress Anna Kendrick tweeted: “I was just talking to someone a few nights ago about how much fun (and fucking difficult) it is to sing Stephen Sondheim. Performing his work has been among the greatest privileges of my career. A devastating loss.”

Becoming obsessed with “Sunday”

In college, we had (like Augustana here does), an independent January term, where students could take a pre-existing class or devise an independent project or off-campus internship. In January 1985, I arranged to intern with a Manhattan-based arts management firm, close to Carnegie Hall, and lived in my grandparents’ Queens home while they were in Florida. It was an insanely exciting month, proving while it was an exhausting thrill to live and work in the city, I wouldn’t want to be there permanently. During that month, I went to five Broadway shows, including “Sunday in the Park With George,” which had opened the previous May, starring Mandy Patinkin as the painter Seurat and Bernadette Peters as his mistress and muse, Dot. I didn’t get to see Patinkin in the part, but it was still an exhilarating revelation, and the musical’s “Finishing the Hat” has become an anthem for many an artist. Some of its lyrics:

And when the woman that you wanted goes

You can say to yourself, “Well, I give what I give”

But the women who won’t wait for you knows

That, however you live

There’s a part of you always standing by

Mapping out the sky, finishing a hat

Starting on a hat, finishing a hat

Look, I made a hat

Where there never was a hat

The song was so central to Sondheim’s career that he based his two major books of annotated lyrics (for me, the Old Testament and New Testament) on it — Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954–1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes was published in 2010, and the second volume, Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981–2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Wafflings, Diversions and Anecdotes, was published in 2011.

The tremendous “Move On” near the close of Act II of “Sunday” brings the modern George (great-grandson of Dot) back to the Parisian island to find inspiration and he is reunited with the 19th-century Dot. She inspires him to create art again and they find the love and connection they never had 100 years prior. It ends:

Just keep moving on

Anything you do

Let it come from you

Then it will be new

Give us more to see

“Sunday in the Park” is such an illuminating window into the motivation and magic of art, and what drives artists. The last line of the show is, “White – a blank page or canvas. His favorite, so many possibilities.” At the time, I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life, but I knew music had to be part of it. I was not going to be a concert pianist, an agent, or (it turned out) a music teacher, but music and the arts has remained a central part of my life since I left college. That January, I also tracked down the legendary Broadway record producer Thomas Z. Shepard, a 1958 Oberlin music alum, who had previously spoken in one of my classes. I wanted his career advice.

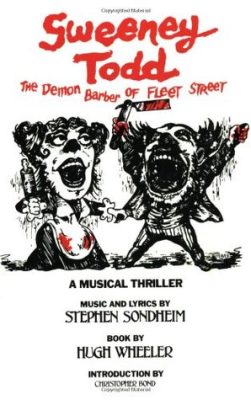

The dark, operatic thriller “Sweeney Todd” (1979) first starred Angela Lansbury and Len Cariou.

Shepard has produced so many landmark original cast albums – including “Sunday,” “Sweeney,” “Company” (1970), the amazing live album “A Stephen Sondheim Evening” (1983),” the stupendous “Follies Live in Concert” (1985) and “The Secret Garden” (1991). I don’t remember specifics of what we talked about, just that I was so nervous to meet him; I recall seeing some of his Grammy awards, and fittingly, on the upright piano in his office was the sheet music for “Move On.” My first steady girlfriend broke up with me that month, so it was extra apt.

Another poignant “Sunday” song – “Children and Art” — played a part in a eulogy I gave at my mom’s funeral. In the original, Dot’s elderly daughter Marie tells the contemporary George how the 19th-century artist incorporated Dot into the “Sunday painting.” In a similar way, my mom lives on through her kids and grandkids, I quoted (pointing to my family members):

There she is, there she is

There she is, there she is

Mama is everywhere

He must have loved her so much

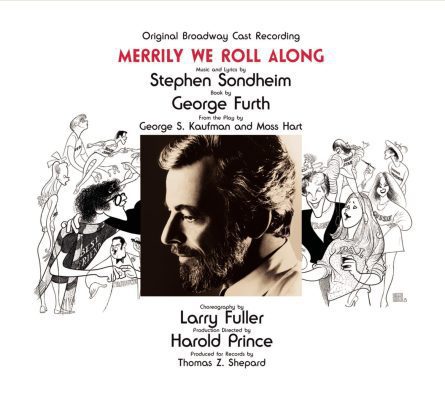

Identifying with “Merrily”

Ever since my senior year of high school, I also was obsessed with Sondheim’s other famous flop, 1981’s “Merrily We Roll Along,” which despite being directed again by partner Hal Prince (who helmed everything during the ‘70s, from “Company” to “Sweeney”), closed after only 16 performances.

Frank Rich – formerly the powerful New York Times theater critic – notoriously wrote of its opening: “As we all should probably have learned by now, to be a Stephen Sondheim fan is to have one’s heart broken at regular intervals. Usually the heartbreak comes from Mr. Sondheim’s songs — for his music can tear through us with an emotional force as moving as Gershwin’s. And sometimes the pain is compounded by another factor – for some of Mr. Sondheim’s most powerful work turns up in shows (”Anyone Can Whistle,” ”Pacific Overtures”) that fail. Suffice it to say that both kinds of pain are abundant in ”Merrily We Roll Along,” the new Sondheim-Harold Prince-George Furth musical that opened at the Alvin last night. Mr. Sondheim has given this evening a half-dozen songs that are crushing and beautiful – that soar and linger and hurt. But the show that contains them is a shambles.

“ ‘Merrily We Roll Along’ has been adapted by Mr. Furth from the second George S. Kaufman-Moss Hart collaboration, a Broadway curiosity of 1934. While the new version is rewritten and updated, it repeats the defects of the original text – even as it adds more of its own. Now, as before, ”Merrily” is about three best friends who reach the top of the Broadway-Hollywood showbiz whirl only to discover, in two cases, that their lives are empty, petty and loveless. The gimmick is to tell the story backwards. The central plot begins with the principals at a present-day party, where they’re at their lowest, most jaded ebb. We end up at a high-school graduation, where the hero vows to uphold all the pure ideals we’ve spent the evening watching him betray,” Rich wrote.

“Merrily We Roll Along” (1981) ran for just 16 performances.

While Sondheim often was asked if his songs were autobiographical, he pointedly responded that he wrote specifically for the book’s characters, and rather than Seurat, it was the songwriters in “Merrily,” that most personally mirrored his trajectory, citing the hopeful, aspirational “Opening Doors” as revealing his story in trying to make it in showbiz.

As Frank, Charley and Mary follow their dreams, they sing in part:

We’re opening doors,

Singing, “Look who’s here!”

Beginning to sail

On a dime.

That faraway shore’s

Getting very near!

We haven’t a thing to fear,

We haven’t got time!

In the kaleidoscopic adventure of that song, a Broadway producer they audition for (originally played by a 22-year-old Jason Alexander), throws some brickbats at the Sondheim stand-ins, singing some of the criticisms leveled at the composer in real life, even riffing off Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “Some Enchanted Evening” melody:

That’s great. That’s swell.

The other stuff as well.

It isn’t every day

I hear a score this strong

But fellas, if I may,

There’s only one thing wrong:

There’s not a tune you can hum.

There’s not a tune you go bum-bum-bum-di-dum.

You need a tune you can bum-bum-bum-di-dum ?

Give me a melody!

Why can’t you throw ’em a crumb?

What’s wrong with letting ’em tap their toes a bit?

I’ll let you know when Stravinsky has a hit ?

Give me some melody!

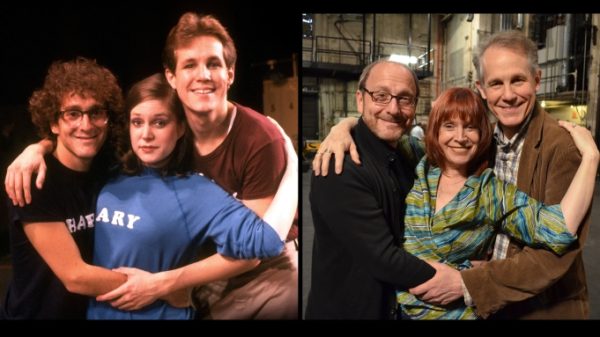

I could go on about “Merrily,” the score is so good, but unfortunately, while Sondheim’s works are routinely revived, there hasn’t been a standout Broadway revival in 40 years. The original Charley, Lonny Price, went on to be a filmmaker, and made a profoundly riveting and heartbreaking 2016 documentary about the musical – “The Best Worst Thing That Ever Could Have Happened.” It’s well worth checking out on Netflix.

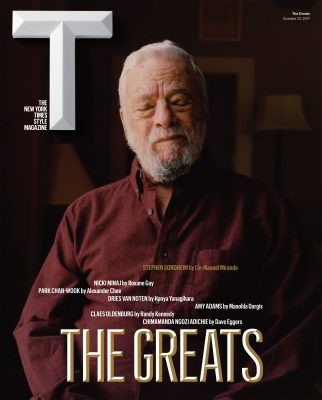

A New York Times magazine cover of Sondheim in 2017.

Like the composer always did (echoing one of his own songs, “I Never Do Anything Twice”), Sondheim didn’t ever want to repeat himself, and constantly strove to create new musicals that were totally different from what he did before. After the resounding success of the 1979 “Sweeney” (a dark, bloody, vengeful and witty melodrama set in Victorian England), “Merrily” was contemporary, and Price shows some tapes recorded for an ABC documentary on Sondheim that never aired, and he watches his puppy-eyed, long-curly-haired young self talk about how being in this show is the greatest thing he can ever imagine happening.

“That’s how everyone in the cast feels. They’re all Sondheim freaks, but they’re also just kids (they range in age from 16 to 25) who have been brought on board to act out Sondheim and Prince’s fearless concept — a musical about a composer, a lyricist, and a critic all growing into middle age, but cast with actors who look young enough to be in a high-school musical,” said the Variety review of the doc. “Major tinkering went on during the previews, but up until opening night, Sondheim, Prince, and company thought they had a brilliant show. Audiences, however, could barely sit still for it, and the critics were savage; the show closed after only 16 performances. Frank Rich, as ardent a Sondheim fan as there is, looks back in sadness at his pan in The New York Times, but stands by it, and he describes the profound confusion the show provoked in audiences. The combination of kids playing adults and time moving backwards was one dislocation too many.”

“Best Worst Thing That Ever Could Have Happened” shows how much the show meant to the actors, as Price caught up with them and related what happened in the years since (Alexander found the most fame, as George Costanza in the TV series “Seinfeld”). There’s “an exquisite fascination and mystique to seeing Sondheim in his prime, looking to write ‘simple’ songs of the kind he did when he was 25,” Variety said. “ ‘Merrily We Roll Along’ remains one of his most entrancing scores, and that’s why it’s one of the most ironic bombs in Broadway history. All the stuff the show’s creators were getting excited about turned out to be awful, but the thing they took for granted — Sondheim’s tunes — could have been the basis for a classic show.”

The leads of 1981’s “Merrily We Roll Along,” left, and how they appeared in the 2016 documentary “The Best Worst Thing That Ever Could Have Happened.”

The stunning songs themselves are far from awful (producing a score more beloved than “Anyone Can Whistle”) and I don’t understand why a story told backwards would be SO confusing. “Merrily” partly took that path to give us an upbeat, “happy” ending, as the young heroes evoke the Sputnik-era optimism, and dream of “Our Time” to make it big. Similarly, Price’s touching documentary closes with the video from the original auditions, when Hal Prince told the cast he had good news for them — they’re all in the show. The boundless joy, hugs and tears of their reaction are priceless. (Another coincidence, one of my Oberlin classmates was Prince’s son Charlie, who became a notable conductor.)

Close to the man in Connecticut

Another peak experience has been my connection with another groundbreaking Sondheim show, “Assassins,” which opened Off-Broadway at Playwrights Horizons on Dec. 18, 1990, and closed on Feb. 16, 1991, a victim in part of the colorful real-life characters who literally take aim to kill U.S. presidents, as then President George Bush was enjoying popularity because of the first Gulf War.

Using the ingenious framing device of an all-American, yet sinister, carnival game, the revue portrays a group of nine historical figures who attempted (successfully or not) to assassinate Presidents of the United States, and explores what their presence in American history says about the ideals of their life and country. The score was written to reflect both popular music of the various depicted eras and a broader tradition of “patriotic” American music. Like a fever dream, “Assassins” imagines the malcontented misfits interacting with each other across time – a climactic scene in the one-act is where John Wilkes Booth (the ringleader among assassins) encourages the motley crew to pressure Lee Harvey Oswald to shoot JFK on Nov. 22, 1963.

At the time of the musical’s premiere, my wife and I lived in Connecticut and I worked for an upscale weekly newspaper based just 10 minutes from Sondheim’s country home in Roxbury (no, I never got to meet him, though I tried). In 1992, a local theater company staged the New England premiere of “Assassins,” and it was mesmerizing, shocking, haunting and hilarious, that I saw it twice. I noticed Sondheim had written a note to the cast that was posted on a bulletin board, and I took down his New York City address, I later tried to get an interview close to his 65th birthday, but he declined in a note, then saying he usually only did interviews to help promote a production. Years later, I did get a more meaningful note from him.

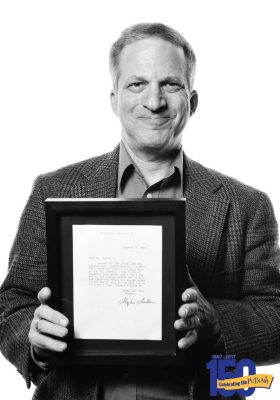

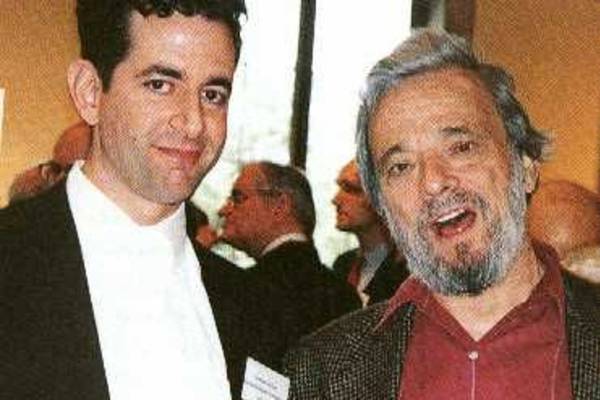

Jonathan Turner with an autographed 2008 note from Stephen Sondheim.

Between about 2000 and 2010, I worked with a former pastor at the Lutheran church in Davenport where I play piano, on writing a new musical based on The Book of Job, my first (and only) full show. It’s called “Hard to Believe,” with a double meaning based on the tragedies that befall Job, and his crisis of faith. Before it was produced by Playcrafters in Moline in 2010, I had the crazy idea that I could get feedback from Sondheim on the work in progress, knowing that he was a mentor to many young composers, and he considered teaching a sacred profession.

Like he sought out advice from Hammerstein in 1945, I hoped to get some sliver of encouragement from The Man. Though again I didn’t succeed, I framed his typed, signed response of Jan. 2, 2008:

“Dear Mr. Turner – Thanks for the letter and the compliments. Unfortunately, I simply don’t have the time to vet your show. As you can imagine, I get a lot of requests like yours, and I can’t say yes to one without saying yes to all, and there are simply not enough hours in the day or days in the week for me to fulfill them all. Please forgive me. Happy New Year anyway…”

A Dec. 1 New York Times piece said Sondheim sent out many similarly short notes, calling him theater’s “encourager-in chief.”

Realizing dreams of “Sweeney” and “Assassins”

Within three years, before the Covid pandemic shut down the world, I was able to realize two long-held dreams – accompanying a live production of “Sweeney Todd” and acting in “Assassins.”

Based on a 1973 British play, “Sweeney” is a horrific tale (with heaping doses of black humor and yearning romance) of a Victorian-era barber who returns home to London after years of exile to take revenge on the corrupt judge who ruined his life. When revenge eludes him, Sweeney swears vengeance on the entire human race, murdering as many people as he can, while his business associate Mrs. Lovett bakes the bodies into meat pies and sells them to the unsuspecting public.” Perhaps composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim’s most perfect score, Sweeney Todd is lush, operatic, and full of soaring beauty, pitch-black comedy and stunning terror. It’s one of the signal achievements of the American musical theater of the last fifty years,” according to stageagent.com.

After accompanying Pleasant Valley High School’s “Chicago” and “Thoroughly Modern Millie,” I was asked to play for a June 2017 production of “Sweeney,” which they had done the previous November, and were taking to the International Thespian Festival at the University of Nebraska. Directed by Bill Myatt, the top-notch cast performed it twice in one day, in a matinee and that evening, and it was one of the most thrilling, challenging experiences I have ever had. The mammoth “Sweeney” score is perhaps Sondheim’s most fiendishly difficult; two hands seem far from adequate to properly play it at one time at one keyboard.

Jonathan Turner played John Hinckley and Sara Wegener was Squeaky Fromme in a 2019 production of “Assassins” at the Black Box Theatre.

What hooks musical theater performers like me is, the satisfaction of his shows come not only from clever, rich and beautiful the music and lyrics are, but how frustratingly hard much of they are to learn – and when you master them, the reward is ever so much greater. It’s a peak achievement comparable to pinning down the essence of any great writer or composer, and revealing that to the world just as they intended.

What’s more, after the Lincoln, Neb., experience (also riding a bus the 5.5 hours each way within the same 24 hours), theater critic Peter Filichia of Music Theatre International gave a glowing review for our “Sweeney,” beginning:

“Hear ye, hear ye, directors of high school musicals! When the time comes for you to retire — be it tomorrow or the latter half of the century — you may well look back on Sweeney Todd as your crowning glory. Do you dare to do it? If your kids have the voices, you almost owe them a chance to perform Stephen Sondheim’s now-legendary score and Hugh Wheeler’s riveting book. As Carl Wallnau of The Young Performers Workshop in Hackettstown, New Jersey has often said (and this is one of my all-time favorite quotations), ‘If you don’t tell kids that something’s impossible, they simply go out and do it.’

Jonathan Turner was in the August 2019 cast of “Assassins” at Moline’s Black Box Theatre.

“I saw it happen through Pleasant Valley High School’s Sweeney Todd, not in its hometown of Bettendorf, Iowa, but in Lincoln, Nebraska at last month’s International Thespian Festival,” he wrote.

Two years later, I was cast as attempted assassin John Hinckley for an August 2019 production of “Assassins” at Moline’s Black Box Theatre. Again, an unforgettable, life-changing experience.

I was thrilled to get a part in this intense, amazing production, my first stage role in 33 years, with a cast packed with tremendously talented actors, who melted perfectly into their parts. Given the depressingly familiar onslaught of mass shootings in the U.S., it was bittersweet to sing the “Assassins” battle cry, “Everybody’s Got the Right (To Be Happy).” There are enshrined rights to free speech and legal firearms, but murder is a whole different game.

Playing the sad, pathetic Hinckley (who was obsessed with movie star Jodie Foster, and identified with aspiring assassin Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver,” who aimed to save Foster’s Iris, a child prostitute), it’s hard to see how his “brave, historic act” would truly impress her. Not only did Hinckley attempt to kill Reagan, but his press secretary Jim Brady and two law enforcement officers were shot during the March 1981 chaos. Brady suffered a serious head wound that left him partially paralyzed for life. His wife became a gun-control leader, and they fought to pass background checks for all gun sales, which became the “Brady Bill.”

The 2019 production in Moline included Tommy Ratkiewicz-Stierwalt (second from left) as Lee Harvey Oswald and Mark McGinn (right) as John Wilkes Booth.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton signed the bill requiring background checks on all gun purchases from federally licensed firearm dealers. Still today, 100 people are shot and killed every day in the U.S., including 61 by suicide.

One of the benefits of great artworks is how they influence our view of current society — either commenting on contemporary events or helping us reexamine our lives through the lens of its subject. “Hamilton” does this with its defense of immigration, and “Assassins” is painfully relevant today by getting inside the twisted minds of its protagonists.

For its first musical in 26 months, the great “Company” this past October at BBT was an expression of love – emanating from both the talent-packed 14 performers on that long, narrow stage, and audiences who were overjoyed to be in the intimate, 60-seat venue with them.

Due to this never-ending global pandemic, the musical’s actors all wore clear, plastic face shields (preferable to cloth masks in both vocal projection and facial expression) and state of Illinois mandates required us in the audience to be masked as well. While the face shields were distracting at first, you got used to watching the tremendously committed performers and marvel at their wizardry and energy. They can’t not do this show, and the power and effect this dazzling act of love had on my life were incalculable.

The Black Box cast of “Company” in October 2021.

Of course, I wished I could have been on stage up there with them, and fortunately, I previously shared the stage with many of the “Company” cast. BBT co-owner David Miller – who also helmed the last Black Box musical, Sondheim’s “Assassins,” in August 2019 – capably directed with care and conviction. The “Company” pit was led by the truly gifted pianist Randin Letendre, who also music directed “Assassins.”

“Company” was led by BBT veteran Tommy Ratkiewicz-Stierwalt as Bobby (who played Balladeer/Lee Harvey Oswald); with Emmalee Hilburn (who was Sara Jane Moore) as Sarah, and Brant Peitersen (who was Sam Byck) as David. And my “Assassins” scene partner Sara Nicole Wegener was the amazing graffiti artist for the new “Company.”

From Sondheim to Larson to Miranda

There’s a direct through-line from Hammerstein, to Sondheim, to Jonathan Larson (“tick, tick…BOOM!” and “Rent”) to Lin-Manuel Miranda (“In the Heights,” “Hamilton,” “Moana,” “Encanto”)

Eight years after the Puerto Rican-American Miranda wrote some Spanish lyrics for the 2009 “West Side Story” Broadway revival, he interviewed Sondheim for The New York Times. “He is musical theater’s greatest lyricist, full stop,” Miranda wrote. “The days of competition with other musical theater songwriters are done: We now talk about his work the way we talk about Shakespeare or Dickens or Picasso — a master of his form, both invisible within his work and everywhere at once.

“Sondheim was one of the first people I told about my idea for a piece about Alexander Hamilton, back in 2008,” he recalled, noting his Manhattan home. “It was in this townhouse, on the first floor. I’d been hired to write Spanish translations for a Broadway revival of ‘West Side Story,’ and during our first meeting he asked me what I was working on next. I told him “Alexander Hamilton,” and he threw back his head in laughter and clapped his hands. “That is exactly what you should be doing. No one will expect that from you. How fantastic.” That moment alone, the joy of surprising Sondheim, sustained me through many rough writing nights and missed deadlines. I sent him early drafts of songs over the seven-year development of ‘Hamilton,’ and his email response was always the same. ‘Variety, variety, variety, Lin. Don’t let up for a second. Surprise us.’”

One of Sondheim’s greatest gifts was that he always surprised us, his legions of fans. And that sweet support and encouragement was clear to Larson, who was born the same year Hammerstein died, and himself passed away suddenly Jan. 25, 1996 (days before his 36th birthday) from an undiagnosed aortic aneurysm. It was also the night before the first off-Broadway preview of “Rent,” so Larson never got to see that rock musical’s huge success – it played 12 years on Broadway, for 5,123 performances, far longer than any of Sondheim’s shows. “Hamilton” (which debuted in August 2015) is currently at 2,005 performances, interrupted by the pandemic, and is close on the heels of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s “Oklahoma!”

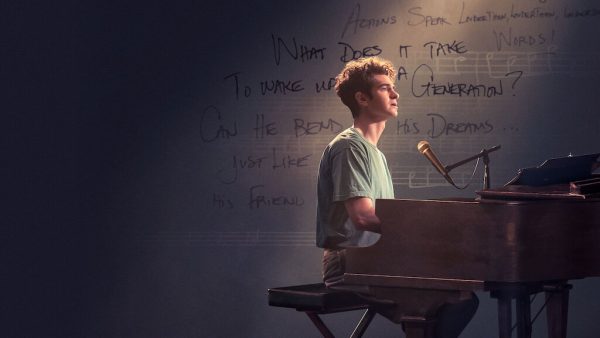

Posthumously, “Rent” won the 1996 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and four Tony Awards. Miranda’s tremendous film directing debut is the recent “tick, tick…BOOM!,” starring the incredible Andrew Garfield as Larson, and the emotional, irrepressible film is a loving homage to both Larson and Sondheim’s influence on him – and by extension on Miranda.

In Vanity Fair recently, he said Larson inspired him to write musicals. The 2001 production of “tick, tick…BOOM!” was a “sneak preview of what my 20s were gonna be,” Miranda said. “It felt like a direct message to me in the 10th row of the audience being like: Hey, Lin, this is gonna be harder than you think. And that very pretty girl sitting next to you is not gonna go into acting. She’s gonna get a real job. And your friends who are all studying theater or film are gonna grow up and find other roads to happiness that are not this thing. And you’re gonna be the only one banging your head against the wall of this childhood dream.”

After Miranda won the Best Musical Tony for “In the Heights” in 2008, he performed as the Larson lead in the musical in 2014, just a few months before he started rehearsals to star in his “Hamilton.”

Sondheim was a key mentor to “Rent” composer Jonathan Larson, left, who died at 35 on Jan. 25, 1996.

“One of the things he gave me was, I think, one of the most important insights into Jonathan, which was Jonathan could be impatient and he could be frustrating and he could be self-obsessed with his work,” Miranda said. “But when he was in a rehearsal room and he was teaching his songs to fellow actors, he was like light and happy and free. He said it was like watching a fish reentered into the water. It was like, oh, that’s what Jonathan was put on this earth to do. And as long as he was doing that, he was in his happy place. And it was everything else was a struggle to get to that happy place. And that was a key insight for us in both the development of the screenplay and in my interactions with Andrew as he was embodying Jonathan.”

In the new movie, Sondheim (played by Bradley Whitford) is a real-life mentor to Larson, and the real Sondheim recorded the answering machine message toward the end of the film. Larson’s song “Sunday” in “BOOM!” is a “love letter to Stephen Sondheim and the creative process,” Miranda told Vanity Fair. “The original ‘Sunday’ in Sunday in the Park With George is this frenzy and cacophony of all the characters onstage, and Georges freezes it. And in that moment, he assembles everyone into the tableau, which is his masterpiece. Jonathan only ever sang this alone at a piano with a rock band. And I have the opportunity as a filmmaker to fill that out as a choir, every bit as loud as the one at the end of act one of Sunday in the Park With George. So what is Jonathan Larson’s dream choir? Because this is Jonathan Larson’s fantasy very openly.

“And so I reached out to the figures that played an enormous role in Jonathan’s creative life and Sondheim alums and other incredible theater alums that, you know, we are the sort of legends that we’re lucky enough to continue to create alongside,” he said.

Bradley Whitford, left, played him in the new movie “tick, tick…BOOM!”

The legacies of Larson and Sondheim are not only in their life-affirming, extraordinary scores, but also appropriately, in nurturing the next generation of teachers and creators.

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts each year gives out Kennedy Center/Stephen Sondheim Inspirational Teacher Awards — which recognize American teachers by spotlighting their extraordinary impact on the lives of students. Award recipients each receive $10,000 and are showcased, along with the former students they inspired, on a website dedicated to inspirational teachers. The awards were created by the Center in honor of Stephen Sondheim’s 80th birthday in 2010.

“Teachers define us,” he once said. “In our early years, when we are still being formed, they often see in us more than we see in ourselves, more even than our families see and, as a result, help us to evolve into what we ultimately become. Good teachers are touchstones to paths of achieving more than we might have otherwise accomplished, in directions we might not have gone.”

There are Larson grants that go to musical theater composers, lyricists, and librettists, or writing teams, early in their career, to support artistic endeavors and safeguard long-term music writing careers. The few grants Larson received inspired him with the professional confidence to continue pursuing musical theater and, ultimately, to finish “Rent,” according to the grant program. Today, Jonathan Larson Grants are awarded to musical writers with the potential to create work that shapes contemporary culture.

Miranda in The New Yorker called his film reflecting Larson “on the verge of turning thirty, and it’s a portrait of an artist trying to find their way. Sondheim was a mentor of Jonathan’s at one of these songwriting workshops. I actually tweeted the recommendation letter that Sondheim wrote for Jon that we found in the archives, which is such a mike drop of a letter,” he said. “If I ever got this letter I would never stop weeping. I sometimes lament how much more writing Sondheim could have done if he weren’t such a generous mentor to so many generations of artists, myself included. But he’s so generous with what he knows, because that’s the gift he got from Oscar Hammerstein II.”

Andrew Garfield plays Jonathan Larson in the movie directed by Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Miranda also has been paying it forward with the Hamilton Education Program of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. A partnership between The Rockefeller Foundation, “Hamilton,” Gilder Lehrman and the New York City Department of Education, launched in October 2015, to bring public school students — mostly those eligible for free and reduced-price lunches — to see the Broadway sensation. Students in New York benefited from an integrated curriculum developed by Gilder Lehrman that touched on their experience of the play.

The program was such a success that The Rockefeller Foundation funded the partnership nationwide. Two United Township High School students in East Moline performed an original rap based on Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” in Chicago, before 1,900 students and teachers who attended the matinee performance of the acclaimed show at the CIBC Theatre.

The education program is available free online — its goal is to help students in grades 6–12 see the relevance of the founding era by using primary sources to create a performance piece (e.g., a song, rap, poem, or scene) following the model used by Lin-Manuel Miranda to create the musical Hamilton. The program consists of classroom activities and digital resources that can be incorporated into a regular curriculum on the founding era. Students participating in the program have the chance to submit their performance piece and be selected to see a performance of Hamilton in New York City. In Chicago, 45 UTHS students got to go Nov. 29, 2017 for just $10 each (the so-called “Ham4Ham” deal, since Hamilton is pictured on the $10 bill).

A theater on Broadway and a new “West Side Story”

Sondheim not only lives on in our hearts, stages, and playlists, but in brick and mortar. The Stephen Sondheim Theatre on Broadway, formerly Henry Miller’s Theatre, was renamed and dedicated in March 2010, on his 80th birthday. Sondheim is one of only three composers whose name adorns a Broadway theater (along with George Gershwin and Richard Rodgers).

While he explored the complexities of love and relationships for decades, Sondheim himself finally found a permanent partner in the last years of life. He came out as gay when he was 40 years old, and at the time of his death, was married to his husband Jeff Romley. Jeff is a Broadway and West End producer who has worked on many shows including The Producers, Hairspray, Porgy & Bess, Sweeney Todd and Company. He has also worked at the William Morris Agency as a theater talent rep and at 41, is 50 years younger than Sondheim. The pair married in 2017 and lived together in Roxbury, Conn.

“The thing about Stephen Sondheim is that there is almost nothing meaningful to write about him, because he captured what was remarkable about himself better than anyone else ever could,” Talya Zax wrote for The Forward. “All you have to do is listen to one of his songs — any one — to see it: The playfulness, the troubled and sublime love for human experience, the profound clarity of observation, the deft, remarkable instinct for beauty.

A scene from the new “West Side Story,” to be released Dec. 10.

“It is apt, in a way, that Sondheim would pass at a moment when his star is more than usually central in popular culture,” she wrote, also noting his godlike status. “He appears in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s new film adaptation of the late Jonathan Larson’s autobiographical musical ‘Tick, Tick… Boom!’ both as an actual character, played by Bradley Whitford, and an artistic inspiration so overwhelming as to be almost messianic: not just a creator of art, but the living embodiment of all that makes art meaningful.”

One of his earliest projects, “West Side Story,” for which he wrote lyrics to accompany Bernstein’s soaring music, is about to premiere in a new film, to finally be released Dec. 10, a year after its original release date.

“It’s the best possible bookend to Sondheim’s career,” Zax wrote. “He entered the world’s imagination with it, a young talent whose words somehow, miraculously, didn’t just match the brilliance of Bernstein’s music, but instilled it with even more beauty. And it was in one of its songs that he established what would turn out to be something of an artistic thesis. ‘There’s a place for us, a time and place for us,’ he wrote. ‘Hold my hand and we’re halfway there/Hold my hand and I’ll take you there.’ It was a bittersweet statement in the context of ‘West Side Story,’ a wishful promise between two lovers who knew, despite their hopes, that they were unlikely to ever find the dreamlike place they sang of. And it turned into something of a guiding light for Sondheim’s work. His musicals created a place where people could experience what it meant to be fully human, for good and for ill. If they would only trust him to guide them, he would take them, for one brief spell — consistently bittersweet, as life is — to a realm where all emotions were uninhibited.”

I cannot wait to see the new WSS – it looks amazing, and so much more true to the intent of the original piece, with an actual teenage Latina playing Maria (unlike the white Natalie Wood, who lip-synched to the songs in the 1961 film). There’s also a Q-C connection to the new Spielberg musical.

Ariana DeBose as Anita and David Alvarez as Bernardo in 20th Century Studios’ WEST SIDE STORY. Photo by Niko Tavernise. © 2020 20th Century Studios. All Rights Reserved.

Brian Hemesath, a 49-year-old native of Calmar, Iowa, and 1994 graduate of St. Ambrose, was the 2019 assistant to costume designer Paul Tazewell on the new remake of “West Side Story.”

“He’s said in interviews, he loves the original film; he just had imagined it differently when he was a kid and he wanted to bring that to life,” Hemesath said in August 2020 of Spielberg and the 1961 movie musical. “I think people are going to be really excited about the film.”

“It’s a lot more realistic,” he said of the new version, filmed July through September 2019 in New York and New Jersey. Hemesath said the original film seems more like a theatrical production.

“It feels more like you’re watching a stage, and this definitely feels like it’s happening in a real space,” he said. “The performers that they have are unbelievable. The girl who’s playing Maria was 17, and the young lady playing Anita, in addition to being an amazing actress, she was in the original ‘Hamilton’; she was in the Donna Summer musical.”

Tazewell was costume designer for the Tony-winning “Hamilton” and “In the Heights,” among several Broadway shows. “He came into this project and his regular assistant was not available and I was fortunate enough to come in and work on that project,” Hemesath said of the film. “It was an amazing project to be part of – such an iconic film, and the fact that Steven Spielberg wanted to remake that film for a long time.”

Rita Moreno – the 89-year-old EGOT winner who was the original Anita – is in the new cast, and “is unbelievable for her age,” Hemesath said. “She’s also one of the producers on the project – just a force of nature. Her history, willing to share stories of what happened and how she ended up in some very iconic films. She certainly was groundbreaking in being one of the first Latina actors featured in film and television.”

“It’s an enormous production,” he said of filming. “It takes quite a machine to get that all together.”

“Something’s coming, something good” – indeed! (See a new WSS trailer HERE.)

Another recent TV highlight of the legend was in mid-September, when Sondheim was a guest on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, who once played Harry in a 2011 New York Philharmonic concert of “Company.” They are clearly admirers of each other, and Colbert touchingly shared the blurb he wrote for the new James Lapine book, “Putting It Together,” all about the making of “Sunday in the Park.”

“When I was 19, I read the lyrics of ‘Putting It Together’ to my mother, to say that this is what I wanted to do with my life,” Colbert read to Sondheim and the audience. “Even though I had no idea of what ‘this’ might be. I couldn’t sing like Mandy Patinkin, I couldn’t compose like Sondheim, I couldn’t write or direct like James Lapine. But like Seurat’s hat, that play was a window from this world to that.”

Sondheim was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama in 2015.

He then addressed Sondheim directly: “I will always be grateful to you for laying out the desire and the beauty of the act of creation itself, regardless of where that may take you.”

“When I read that, I was touched, and I’m touched again,” Sondheim replied, visibly and audibly choking up. (Watch the beautiful interview HERE.)

In case you’re curious, these are the total performance runs of all Sondheim shows:

- “West Side Story” (1957): 732

- “Gypsy” (1959): 702

- “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum” (1962): 964

- “Anyone Can Whistle” (1964): 9

- “Do I Hear a Waltz?” (1965): 220

- “Company” (1970): 705

- “Follies” (1971): 522

- “A Little Night Music” (1973): 601

- “Pacific Overtures” (1976): 193

- “Sweeney Todd” (1979): 557

- “Merrily We Roll Along” (1981): 16

- “Sunday in the Park With George” (1984): 604

- “Into the Woods” (1987): 765

- “Assassins” (1990): 73 Off-Broadway, 101 Broadway revival (2004)

- “Passion” (1994): 280

- “Road Show” (2008): 45 Off-Broadway

The former Henry Miller’s Theatre on Broadway was renamed the Stephen Sondheim Theatre in 2010.